This web page has the First Edition of the Tiddlywinks: The Classic Victorian Pastime: On Target for the 21st Century.

The Second Edition, entitled Tiddlywinks • Origins and Evolution of the Noble & Royal Game, is now available.

- Article name • Tiddlywinks: The Classic Victorian Pastime: On Target for the 21st Century

- Edition • First

- Author • Rick Tucker

- Original publication date • October 1996

- Publisher • American Game Collectors Association

- Article published in publication • Game Researchers’ Notes

- Publication ISSN • 1050-6608

- Publication page numbers • illustrations and content appearing on the cover, on pages 5552 to 5561, and also on the back cover.

- Scanned issue online • Game Researchers’ Notes, October 1996

This article was originally published in the American Game Collectors Association‘s Game Researchers’ Notes, ISSN 1050-6608, October 1996, with illustrations and content appearing on the cover, on pages 5552 to 5561, and also on the back cover.

In this web version of this article, additional images have been incorporated that did not appear in the original publication. Please note that the AGCA is now known as the Association for Games & Puzzles International.

A substantial majority of the information provided in the original 1996 article remains accurate to this day. However, quite a bit more background information has been gathered since. An update is warranted, and is in the works.

This article was originally posted on the Internet on 3 May 1997, was updated on 2 April 1999, and then with updated images and links on 9 and 15 September 2006, plus a few more updates on 24 November 2006, and also on 13 July 2014. In June 2018, after the website transitioned to a new web hosting provider, all of the images in this article were replaced with higher resolution images, plus images were provided for additional games mentioned in the article. In 2020, additional updates were introduced to the online version of this article. In 2022, the online version was updated during a rehosting with new web authoring tools.

Tiddlywinks: The Classic Victorian Pastime: On Target for the 21st Century

By Rick Tucker

© 1996-2022 Rick Tucker. All Rights Reserved

“One should make a serious study of a pastime”—Alexander the Great [1]

The Preface

I’ve played tiddlywinks for 24 years, ever since I ventured into a dormitory at MIT on my first day as a freshman and encountered (no pun intended) the local denizens on their hands and knees shooting winks across the carpet and down the stairs. (It really isn’t normally played on the floor, actually.) I was captivated at the congruence (technical term, sorry) of the ivory towers of MIT housing the noble sport of tiddlywinks, and amazed that MIT might, perhaps inadvertantly (but not always), lend credence to a sport enmired in such a mischievous stereotype. Tiddlywinks appealed to me because of its unique character, because it is almost universally known, and because it demands precise dexterous skills, while also requiring strategy and tactics, and also a measure of luck.

And so, what follows is the first definitive history of tiddlywinks boxed games. There is a history in all men’s lives.[2] I invite and expect to hear from game collectors and historians to help me add to, revise, and where necessary, fix errors in this history. I also invite you to visit my tiddlywinks web pages at https://www.tiddlywinks.org, where this article will appear subsequent to its publication in Games Researchers’ Notes, with all the photos in living color.

— Rick Tucker, 31 October 1996

Setting the Stage: The Oft-Ridiculed Game

Have we sold our precious heritage in exchange for frivolity and a game of tiddlywinks?".

Letter by Lillie Struble in Library Journal [3].

This was the most unkindest cut of all. [4]

"A 15th-century Donatello bronze,The Madonna and Child, served the Fitzwilliam family as a tiddlywinks bowl until the Victoria and Albert Museum [London] recognized its importance"

ARTnews [5]

"Even in the matter of nursery games the Victorian child took things very seriously. There were some board games, however, which provided little or no intellectual stimulus. Chief among these was […] tiddlywinks, whose apparent inanity (to the uninitiated) is often regarded as the ultimate in useless activities."

James Mackay [6]

Prince Philip once suggested that tiddlywinks be included in the Olympics. To which Ian Wooldridge of the Olympic Committee responded: "At the risk of propagating royal support for tiddlywinks, a game of the utmost tedium played by anti-athletes too tired or apathetic to get up off the floor, I have to concede that his argument makes sense.",

British Airways magazine. [7]

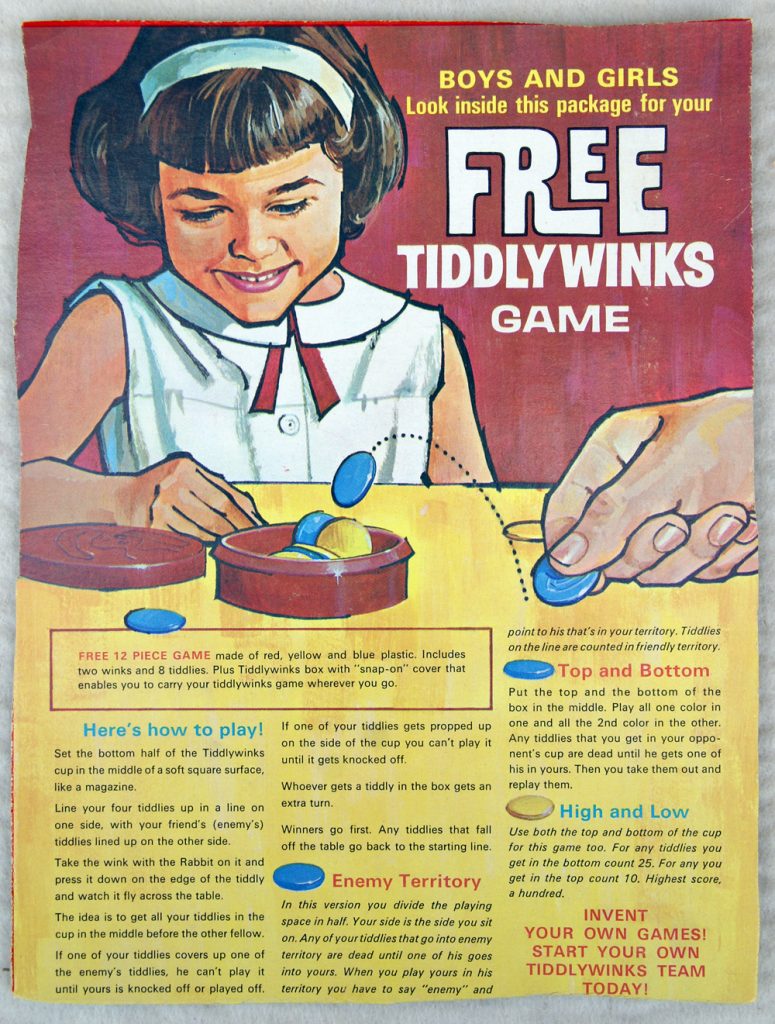

"The research described in this chapter concerns a well-known children’s pastime, the game of tiddlywinks, where the idea is to take one counter and press it on the edge of another, to make the latter jump. Because this is extremely simple, the research centered less on cognizance of the movements actually carried out and more on conceptualization of the action in general and, above all, of its results on the object."

Jean Piaget [8]

All the world’s a stage. And all the men and women merely players. [9] Let’s return to the beginnings of tiddlywinks, back before the Internet (1969), TV (1923), radio (~1906), and even teddy bears (1902). However, the lights were on, and the telephone had been invented less than 15 years before… But wait, just a little context is required as introduction.

On to: The Intrigue

Tiddlywinks presents a paradox. It is unique and it is generic. It is also a plural noun which is singular in construction [10], another paradox of sorts. It is conceptually simple enough for most people to identify and to understand, and yet an extraordinary number of variations exist and remain to be created. Tiddlywinks has perhapsthe most pervasive and negative stereotype of any game, and yet it was a rampant adult fad in the US and England for nearly a decade in the 1890s and to this day is played competitively with fervor by a coterie of well-educated winkers with a propensity for pubs and drinking games. The little foolery that wise men have makes a great show. [11]

Its name derives from British rhyming slang for an unlicensed pub (tiddlywink and also kiddlywink), and yet the name was trademarked in 1889 as TIDDLEDY-WINKS [12], and has gone through dozens of spellings since. The general concept of tiddlywinks, that of flicking a wink with another instrument to make the wink flip into the air, is very basic, and yet there are over eighty approved patents known, starting in 1889. Tiddlywinks was an adult craze in the 1890s, then fell into “disrepute” as a simpleminded children’s game, and yet it has been played since 1955 by adult winkers who were graduated from places with names such as Cambridge University (in England), MIT, Oxford (again, England), Cornell, and Harvard.

Game collectors have traditionally derided generic games since they are produced in great quantities and are often found in dubious condition. Yet, since tiddlywinks is a generic game, there are countless variations in game design, cover art, and the quality and materials of manufacture. Editions exist from the elite publishers (such as McLoughlin and Horsman) with superb lithography, detailed rules, and hand-made parts. And on the other hand, cheap versions abound that have compression plastic winks with burrs and cheap cardboard. However, the cover art, ultimately, is always intriguing, since it reflects the age and day of the set’s debut, from the Victorian parlor to the depression to World War II to the space age. So far, I have recorded over 130 known publishers of tiddlywinks games, with more being uncovered every day (in fact, two new ones today! (28 October 1996)).

As of 9 July 2022, Rick Tucker has identified 421 publishers of tiddlywinks games, with a total of 1688 games and variations among them.

The Rules

As it turns out, the basic elements of the rules of tiddlywinks have changed little since its invention in 1889. The game pieces of tiddlywinks are the winks and the shooter, which has been called many things, including a tiddledy, but nowadays is called a squidger. Over the years, winks have been made of ivory, bone, celluloid, wood, plastic, and even metal. Winks have been round, rings (quoits), square, and horseshoe-shaped. Squidgers are typically round discs, but have also been square, pointed, tennis-racket-shaped, and golf-club-shaped.

The key criterion (technically speaking) for declaring a game to be a tiddlywinks game is that the shooter is used by a human and is applied to a flat wink with a stroke that has a substantive downward component. This leaves out games where an instrument is used with a mainly horizontal stroke, such as in marbles, and omits games where the squidger is directly attached to the wink.

Though this be madness, yet there is method in ’t. [13] The two key ingredients of tiddlywinks rules that were in effect in 1890, for most varieties thereafter, and remain intact today are:

The offensive shot is shooting a wink toward a target and having the wink land on or in the target. In modern terms, when a wink lands inside the targeted cup, it is deemed potted and earns more points.

The defensive shot is shooting a wink so it lands on top of an opponent wink. The opponent wink cannot be used by the opponent while it is covered. In modern parlance, the opponent wink is said to be squopped. In rules from the 1890s, it was not proper to intentionally cover an opponent’s wink with yours, but if it did happen, perhaps accidentally, the opponent still was not allowed to shoot his wink.

The Game’s Afoot [14]

Tiddlywinks was first patented in England by Joseph Assheton Fincher of London as A New and Improved Game. The patent application was filed on 8 November 1888, the complete specification left on 8 August 1889, and it was accepted on 19 October 1889 (England patent 16,215 in 1888.) Fincher applied for TIDDLEDY-WINKS as a trademark in England on 29 January 1889, and it was approved on 15 May 1889 (# 85,800). A set is known to exist with the label “Joseph Fincher, Inventor”, although Fincher is not at all well known as a games publisher.

Fincher’s pivotal role as the owner of the first tiddlywinks patent and thereby as the catalyst in setting the world on fire with tiddlywinks fever and fervor (at least for the next decade) may have been purely an opportunistic or perhaps accidental move on his part. As it turns out, Fincher also patented (in 1890) “Improvements in Sleeve Links”. For the record, sleeve links are also known as cufflinks. Ho hum. And in 1897, Fincher tried to patent a variety of candlesticks, but the application was rejected. Never mind. We will always remember Fincher as the inventor of the unique game of tiddlywinks.

Over eighty patents have been approved for tiddlywinks games since Fincher’s application. In fact, the US Patent and Trademark Office has a subclass expressly for tiddlywinks (Class 273: AMUSEMENT DEVICES, GAMES; subclass 317: AERIAL PROJECTILE, TARGET THEREFOR, OR ACCESSORY; subclass 348: Target; subclass 353: Tiddlywink game). And there have been about 84 patents worldwide to date for tiddlywinks games, including 52 in the US.

1890: The Year of Winks Rampant

Now let us return to 1890. The name of the game quickly fell into the public domain starting in 1890. The golden era of tiddlywinks as a craze, a fad, began and lasted for nearly a decade. Fleet the time carelessly, as they did in the golden world. [15] But the game was still spelled Tiddledy Winks then, and some still spell it that way even today, even though the definitely preferred modern spelling is tiddlywinks. The tiddlywinks spelling is known to have been used as early as 1894, but wasn’t dominantly common until the 1950s.

The first U.S. tiddlywinks patent, # 432,170, actually was from an Englishman, George Scott, who had already patented, in England, a golf version of the game. (The U.S. application was on 6 June 1889, approved 22 March 1890 .)

The British journal Notes and Queries had a query in its 18 January 1890 issue (7th S. IX): “Can any of your correspondents inform me what is the derivation of the word ‘kiddlewink,’ or ‘tiddledy winks’? A friend tells me in the Midland Counties it denotes a house where beer is sold without a licence. Lately a game has been introduced here bearing the name of ‘Tiddledywinks.’—M.D., Lamaha House, Georgetown, Demerara” [in British Guiana].

The earliest documented American date for a published item actually using the word “tiddledy winks” is 14 August 1890, when McLoughlin Brothers copyrighted “Directions for Playing The American and English Game of Tiddledy Winks”. (Tiddlywinks patents did not refer specifically to “tiddlywinks” or “tiddledy winks” until around 1949.) And so what was the difference between the American and English games? That shall remain a mystery for now. An element of intrigue is essential to any pursuit. (Sorry, that is not from Shakespeare!).

Shortly thereafter, U.S. inventor Charles N. Hoyt of Brooklyn, New York successfully patented two versions of tiddlywinks in 1890-1891. The first patent (# 441,099, filed 22 August 1890 and approved 18 November 1890) was directly in his name, but the second patent (# 453,480, filed 23 October 1890 and approved 2 June 1891) was registered as “Charles N. Hoyt, of Brooklyn, Assignor to McLaughlin [sic, should be McLoughlin] Brothers, of New York, N.Y.”.

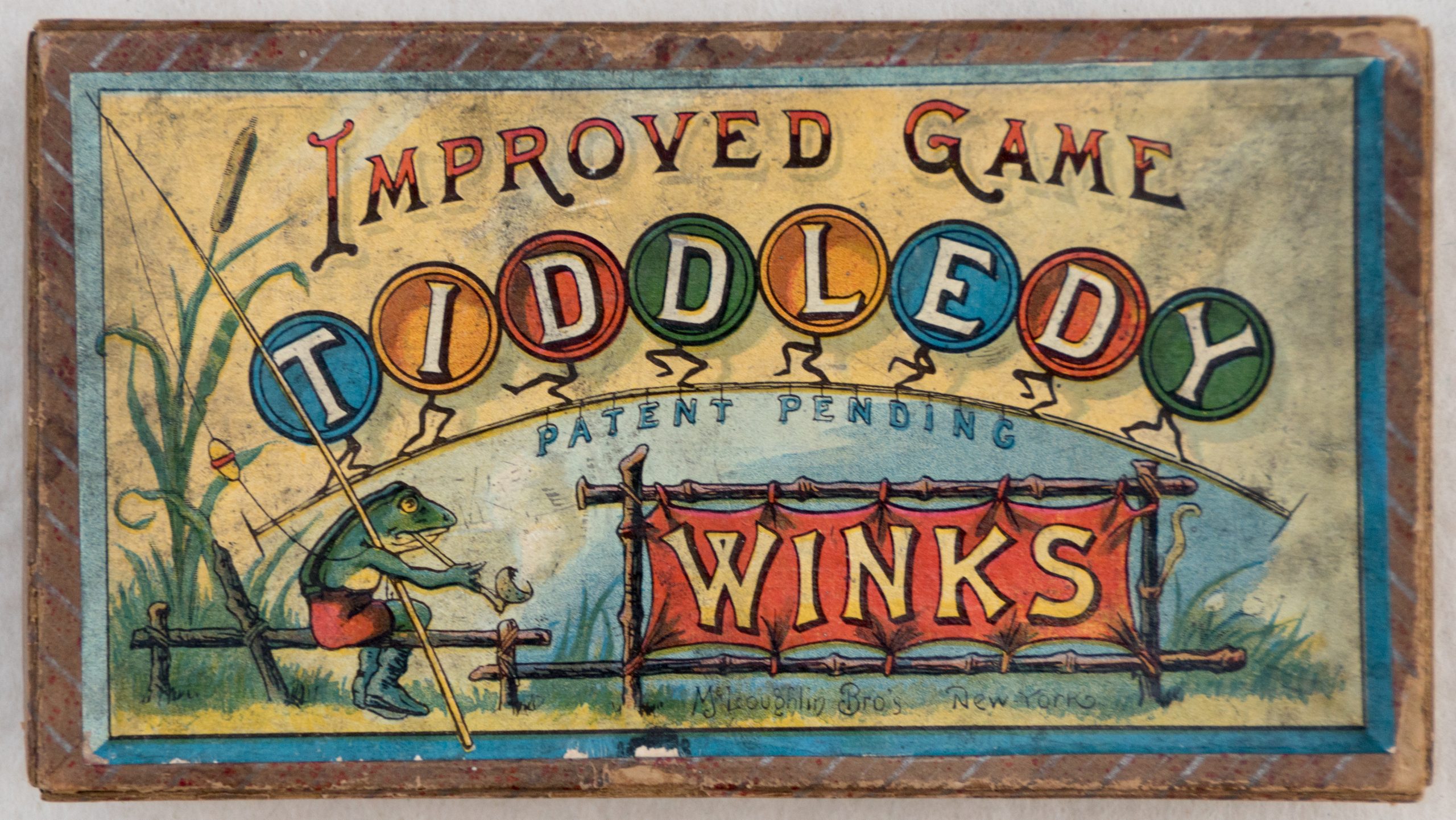

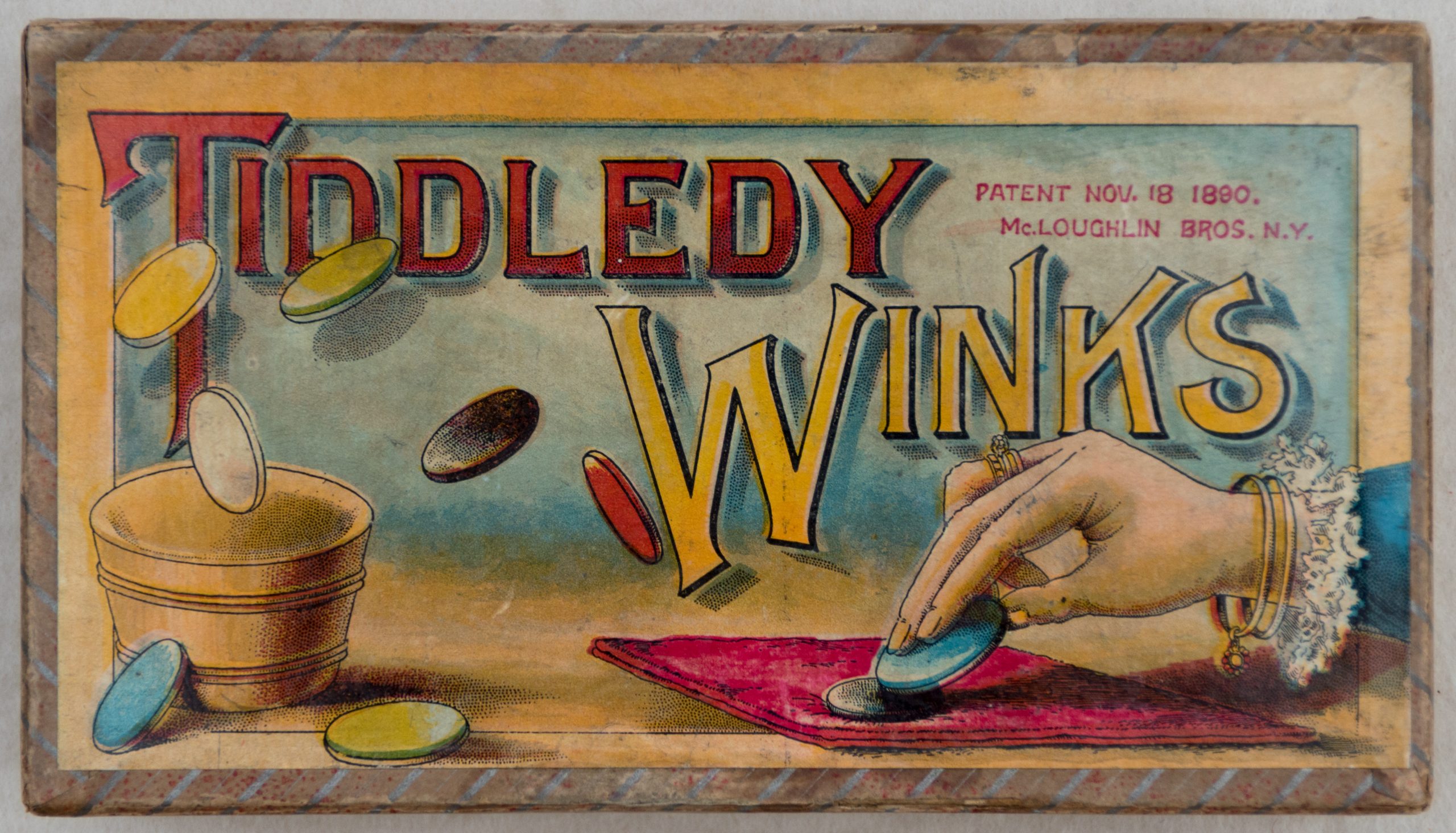

The drawing from the first (1890) Hoyt patent depicts a cushioned shooting pad which exactly matches the large (4-inch by 5-inch) sewn-together felt pads found in most of the early 1890s McLoughlin Bros. sets, and about which the patent specifically states “I prefer to construct said pads by placing one or two thickness of felt between two pieces of flannel and stitching, hemming or binding them together around the margin”. Following are several McLoughlin sets from around 1890, some marked “Patent Pending”, and some marked “Patented Nov. 18, 1890” (i.e., the first Hoyt patent).

Rick Tucker Tiddlywinks Collection

Licenseable per Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

Rick Tucker Tiddlywinks Collection

Licenseable per Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

In the meantime, competition among games manufacturers for newer and better tiddlywinks sets and varieties was becoming quite fierce. In modern winks argot, any variation from the official modern tournament rules is deemed a perversion. The most successful perversions are tiddlywinks versions of sports, such as bowling, tennis, horseshoes, basketball, baseball, etc. (to be described in short order here). The early 1890s saw a patent frenzy to claim unique niches in the tiddlywinks marketplace, plus a few trademarks.

The earliest reports of tiddlywinks innovations appear in The American Stationer, a trade magazine for stationery storekeepers who sold parlor games. The first notice about tiddlywinks appeared in the 18 September 1890 issue:

A NEW GAME.

In "Tiddledy Wink Tennis" E. I. Horsman, 80 William street [New York City] has brought out a very pretty and lively parlor game, which will furnish sport for tennis players during the season when they are debarred from exercising their skill in the open air. "Tiddledy Winks," as originally brought out, is full of amusement, but the new game is infinitely more engaging, and besides, it offers a considerable field for the display of nice calculation and skill.

(Author’s note: I should add at this point that I am a willing purchaser of any Horsman tiddlywinks sets, Jr. or not!)

Indeed, Edward Imeson Horsman, Jr. (Brooklyn NY) clearly thought he had a gold mine here, since he submitted a patent application for PARLOR-TENNIS on 22 September 1890, which was swiftly approved on 9 December 1890 (# 442,438), and then on 24 September 1890 he copyrighted “Tiddledy Wink Tennis—Rules for the Game”. These would be the last patents, copyrights, or otherwise for tiddlywinks sets in his name, although he did come out with several other editions created by others… as we shall see.

Rick Tucker Tiddlywinks Collection

Licenseable per Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

Rick Tucker Tiddlywinks Collection

Licenseable per Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

And on 9 October 1890 in The American Stationer:

E. I. Horsman, 80 William street, is wearing a 7x9 smile these days, notwithstanding he has set the whole world by the ears with his "Tiddledy Winks" tennis, and dealers are fairly tumbling over each other in their haste to get orders in early. […] He cannot manufacture the games fast enough, however, to keep up, and has adopted the plan of sending a dozen to dealers who order a gross […].

This fellow’s wise enough to play the fool, And to do that well craves a kind of wit. [16]

In the meantime, John D. Champlin, Jr. and Arthur E. Bostwick published The Young Folks’ Cyclopædia of Games and Sports (Henry Holt & Co., New York) which is dated in the foreword as 7 November 1890 and as 1890 on the cover page. This book contains the first TIDDLEDY WINKS rules published in a book in the US.

And in the 4 December 1890 edition of The American Stationer:

"See that bundle of letters?" said E. I. Horsman, the great "Tiddledy Winks Tennis" promoter […]. "Well, there are sixty-five of them, every one orders for my favorite game, and they have got to be answered before I go to my dinner […]"."Tiddledy Winks Tennis" is a great thing, I tell you, but I cannot stop to explain why just now. Come again—after the holidays, when the rush is over—and we will confer together on the subject."

The American Stationer of 18 December 1890 reports that:

The dealers are still worrying the life out of E. I. Horsman, 80 William street, about "Tiddledy Winks Tennis," although it must be said he preserves a wonderfully comfortable appearance and smiling countenance for a man who thinks of "Tiddledy Winks" all day and dreams about it all night. He declares however, that he believes people will go right on buying the game regardless of the close of the holiday season, and he thinks there will be no rest for him until every man, woman and child in the United States has one, and he is afraid that by that time Europe will have heard of it, and he will have fresh troubles trying to understand what they want. However, he does not look as though he would mind a babel of tongues very much if "Tiddledy Winks" was involved.

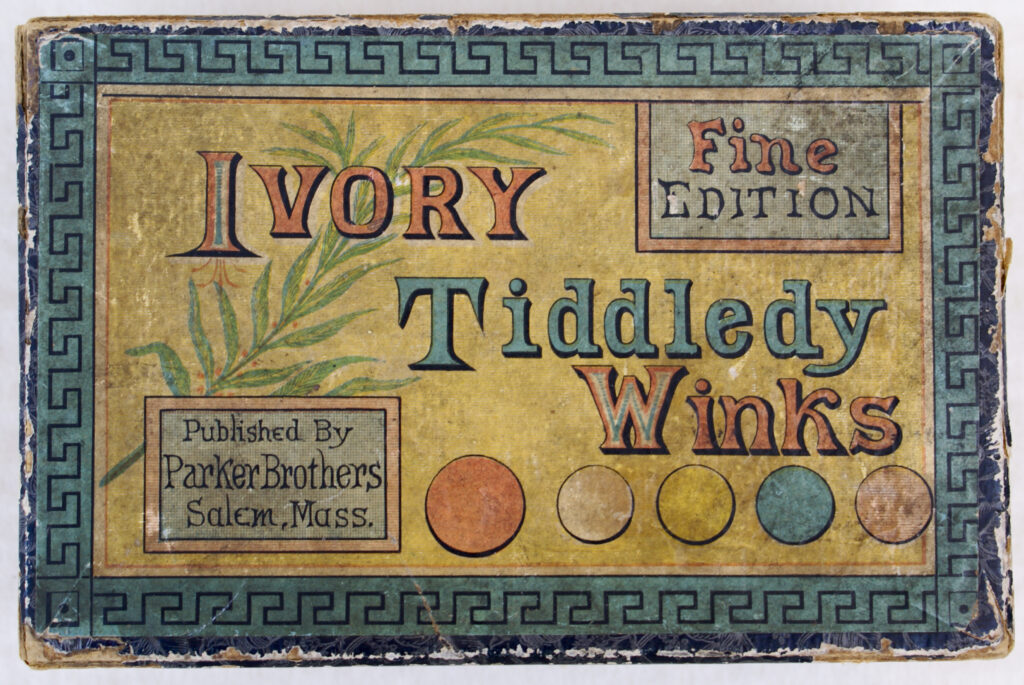

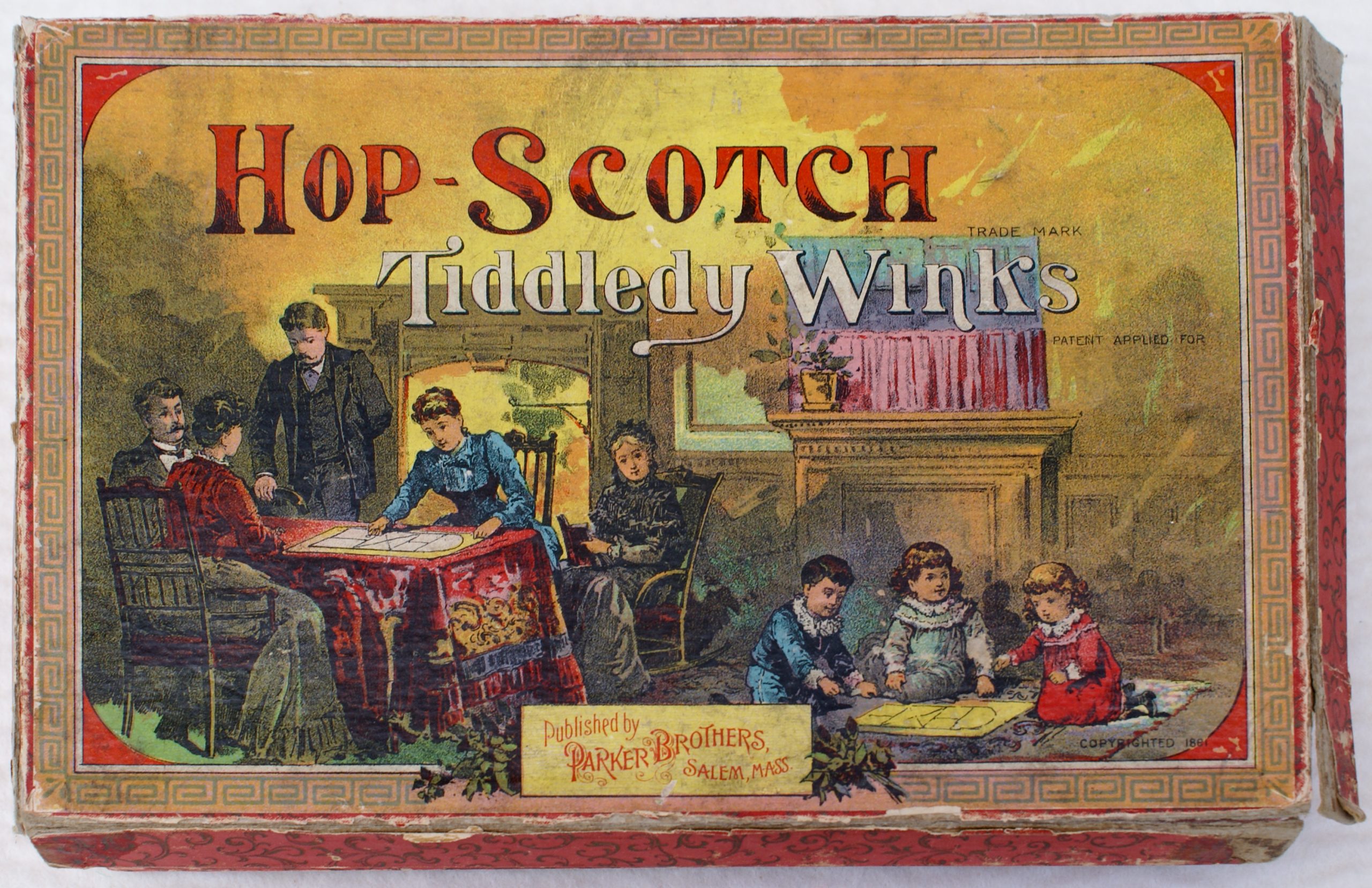

Parker Brothers

One of George Parker's first winning moves had been opening up trade with his English counterparts. [...] When word reached him of the success of a funny little flicking game being played everywhere in Queen Victoria’s country, he grabbed the U.S. rights. The game was called the New Round Game of Tiddledy Winks and was sold by the firm of J. Jacques Jaques and Son. It consisted of a small pot, made of wood or glass, and circular counters made of bone. The aim was to flick each smaller “wink” into the pot by pressing on its edge with a larger counter (“tiddledy” or “shooter”). With a bit of skill and dexterity, even a child could learn to launch the little winks toward the pot from several feet away. The game became one of the first novelty activities to sweep the country. Parker Brothers immediately applied for a U.S. trademark for the name Tiddledy Winks. Fourteen editions appeared in the following year’s Parker Brothers catalog, with prices ranging from twenty-five cents to $1. George wrote proudly of the “continuous hold” the game had on “little ones.” Protecting his hold on its rights was another matter. The trademark did not clear, being deemed generic. During the next few years, while Parker Brothers’ winks were being flicked everywhere in the nation and “made a considerable sum,” Parker Brothers had to share its rewards with many other makers that honed in on the vogue for Tiddledy Winks. Milton Bradley, Selchow & Righter, McLoughlin Brothers, and several smaller firms quickly marketed their own versions of the game that George had purchased in England.

Phil Orbanes, The Game Makers • The Story of Parker Brothers from Tiddledy Winks to Trivial Pursuit, Harvard Business School Press, © 2004, pages 24–25

Principle had guided George Parker well in the past, and the experiences of recent years honed another for him. Principle 3 became “Play by the rules, but capitalize on them.” He first learned this principle by watching the way his competitors capitalized on the Tiddledy Winks fad.

Phil Orbanes, The Game Makers • The Story of Parker Brothers from Tiddledy Winks to Trivial Pursuit, Harvard Business School Press, © 2004, page 30

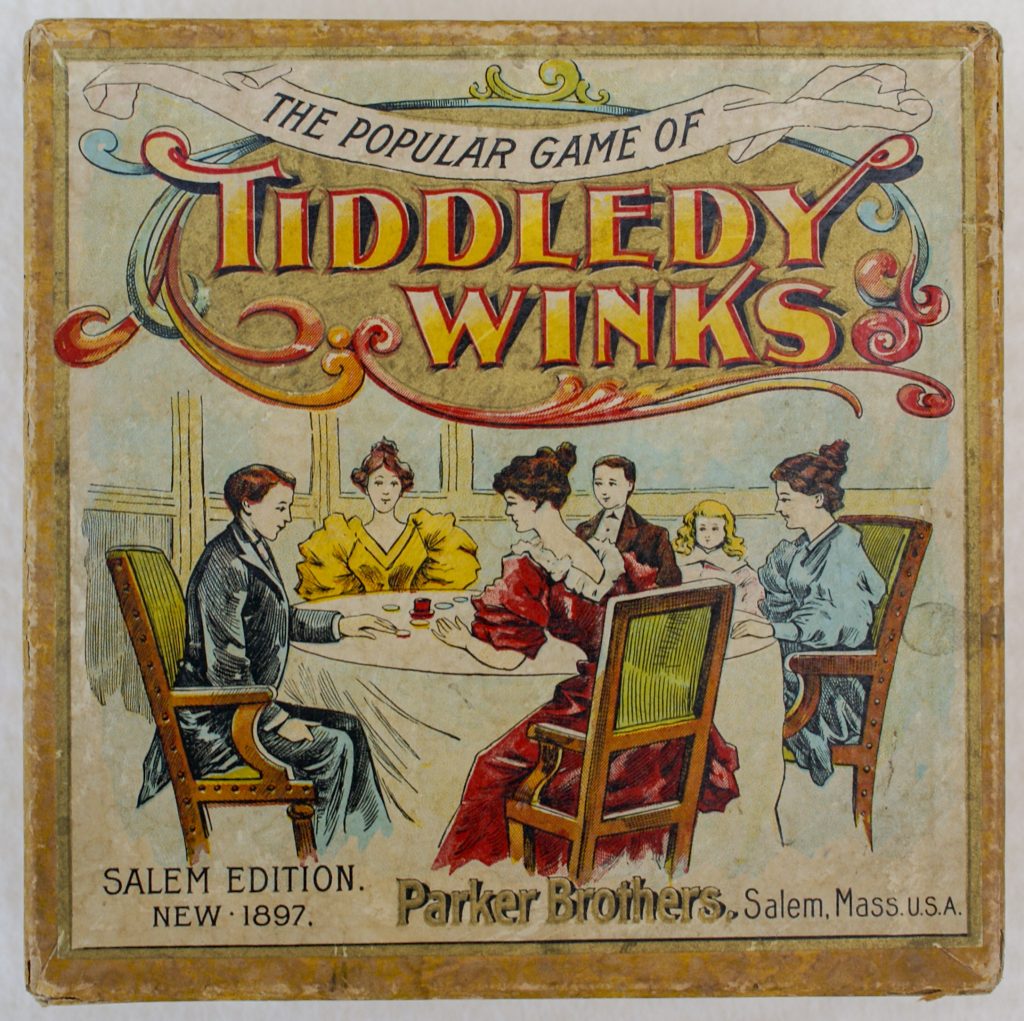

Tiddledy Winks debuted in Parker Brothers’ 1891 catalog, with 11 editions ranging in price from 10 cents ($3.12 in 2022 dollars) to $3.50 ($119.19 in 2022 dollars). Various materials were used for the winks and squidgers in these sets: bone, vegetable ivory, celluloid, composition, and wood. Ivory is listed for edition no. 36, though that’s likely to be vegetable ivory rather than real bone ivory.

A Rash of Sports Simulations

In addition to tennis and golf, a slew of other sports succumbed to tiddlywinks frenzy, starting soon after 1890, and continuing to this very day. These most brisk and giddy-paced times. [17]

Jasper H. Singer copyrighted the rules for “Tiddledy Winks Quoits” on 31 January 1891. A few days later, 5 February 1891, Dock D. Harr applied for a patent (# 464,098) for a GAME-BOARD which involves

[…] placing a ring E’ upon a shooting cushion D and bearing hard upon the edge of the ring with the shooting implement in a downward direction, as indicated by the arrow. This will cause the ring to spring forward. […] The object of each player is to shoot his rings so that they fall over the central pin in the cup.

If you have never tried shooting a plastic or wooden or ivory ring (a quoit) with a disc, you might not think that it would fly through the air very well, but in fact, it does—very well. The patent was approved on 1 December 1891, and in the meantime, Dock. D. Harr copyrighted “Quti-Quoits” on 9 November 1891.

But wait! The American Stationer of 26 February 1891 illustrates Ring-A-Peg, a tiddlywinks quoits game, in which:

[…] a circular board containing a number of upright pegs is placed on a cloth in the centre of the table. The game may be played by two, three or four persons, each player being provided with five rings made of bone brightly colored and a square piece of the same material called the ‘ringer,’ the latter being used to snap the rings upon the upright pegs. […] The inventor of the game is John H. B. Trainer. […] The manufacturers are Geo. B. Leiter & Co., Williamsport, Pa.

And (not so) curiously enough, E. I. Horsman came out with Ring-A-Peg, marked “PAT. APPLIED FOR”, with his “E.I.H” in a diamond mark.

![[+template:(Tucker Tw ID • [+xmp:title+] — publisher • [+iptc:source+] — title • [+xmp:headline])+]](https://tiddlywinks.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/HOR-04v2-DSC00300-768x762.jpg)

Rick Tucker Tiddlywinks Collection

Licenseable per Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

![[+template:(Tucker Tw ID • [+xmp:title+] — publisher • [+iptc:source+] — title • [+xmp:headline])+]](https://tiddlywinks.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/HOR-04v2-DSC00310-1024x583.jpg)

wooden target, winks (quoit rings), squidger (square bone)

Rick Tucker Tiddlywinks Collection

Licenseable per Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

Rick Tucker Tiddlywinks Collection

Licenseable per Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

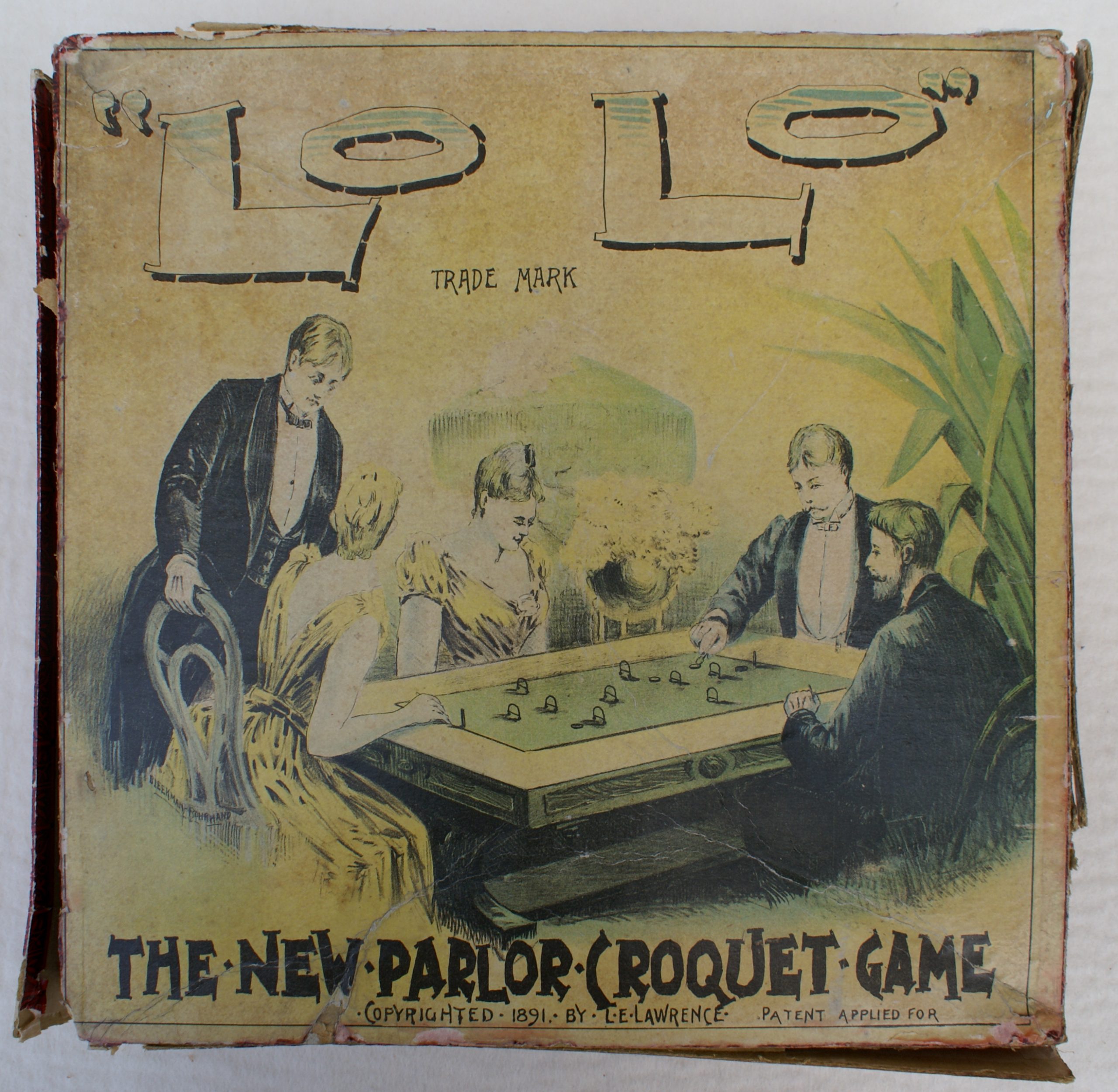

McLoughlin Brothers copyrighted the rules for “Tiddledy Wink Croquet” on 6 April 1891. I have not yet seen this edition. But E. I. Horsman came out with LO LO THE NEW PARLOR CROQUET GAME [18] (The American Stationer, 22 October 1891) where “colored disks represent the [croquet] balls and the ‘mallet disks’ are used to snap them into positions or through the arches”. This Horsman set is labeled with “Copyrighted 1891 by L. E. Lawrence”.

Rick Tucker Tiddlywinks Collection

Licenseable per Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

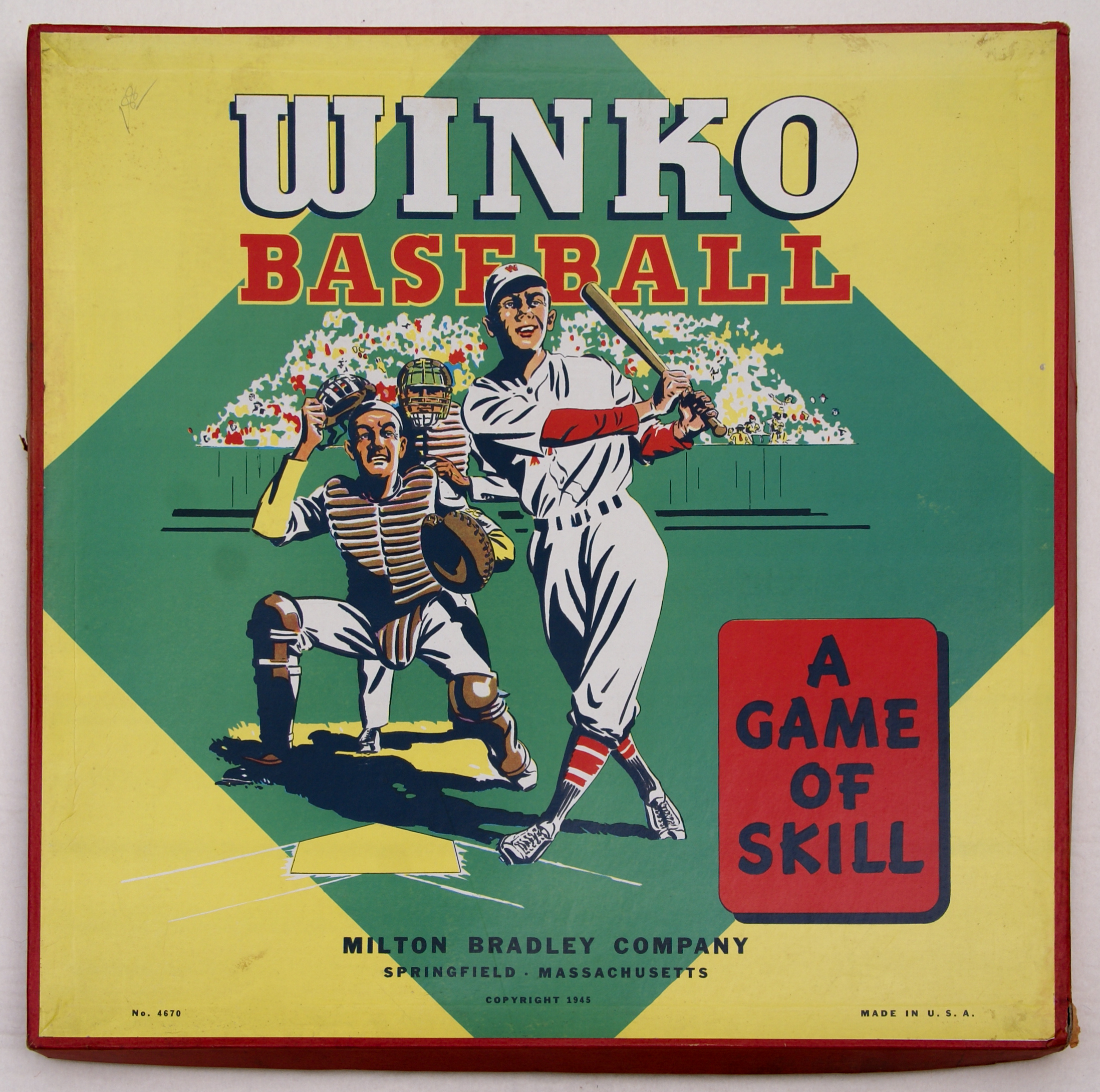

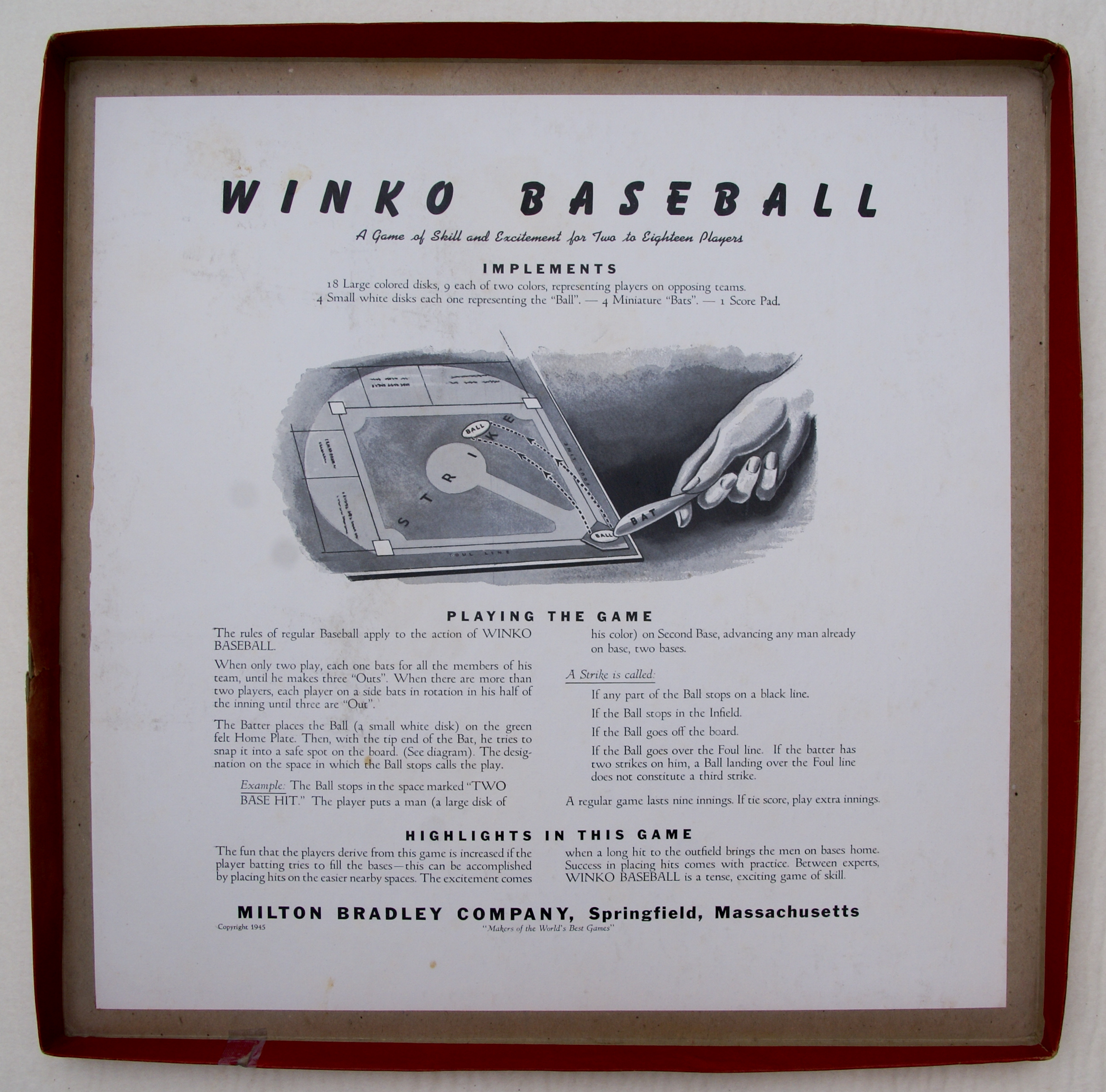

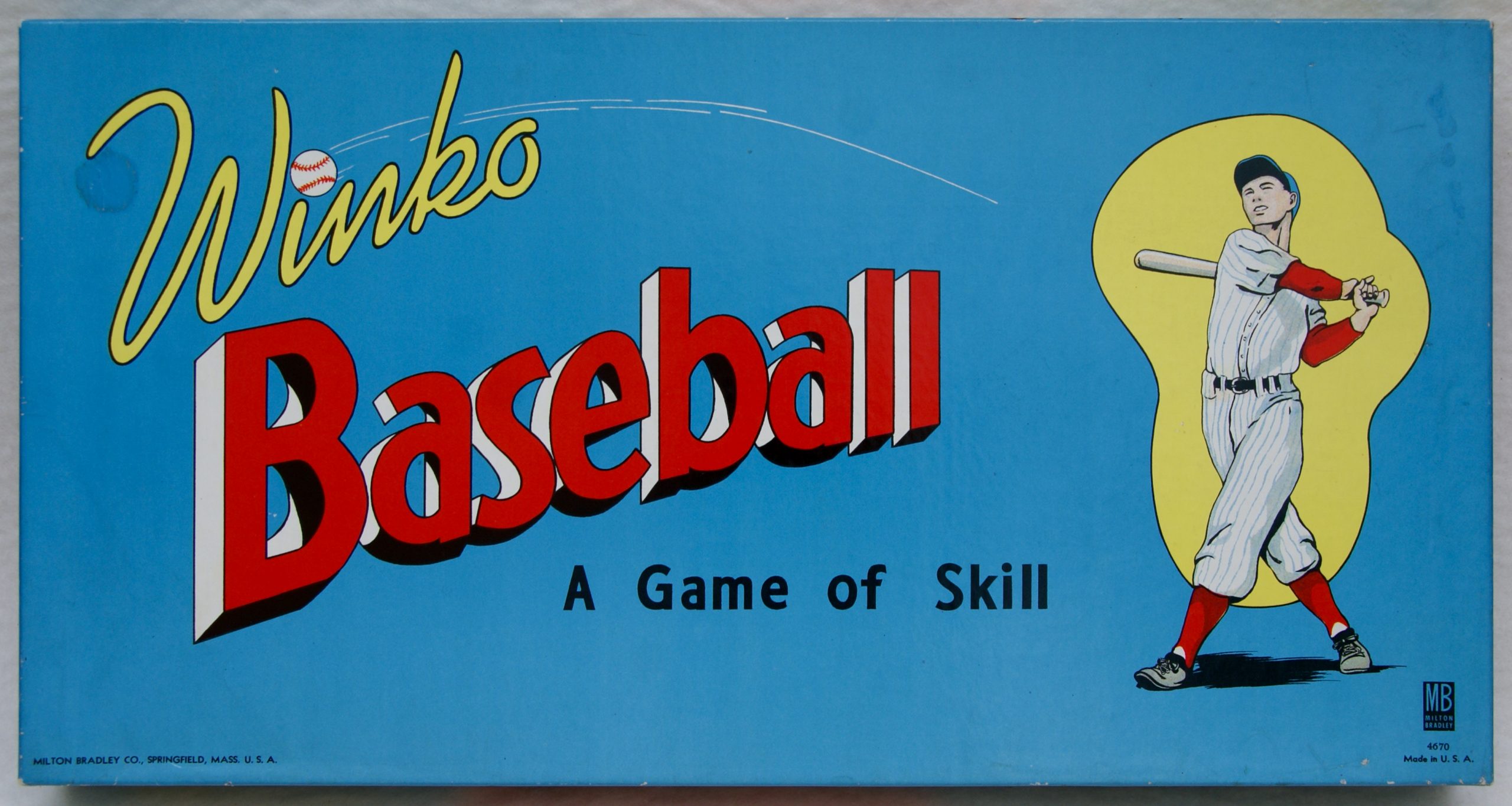

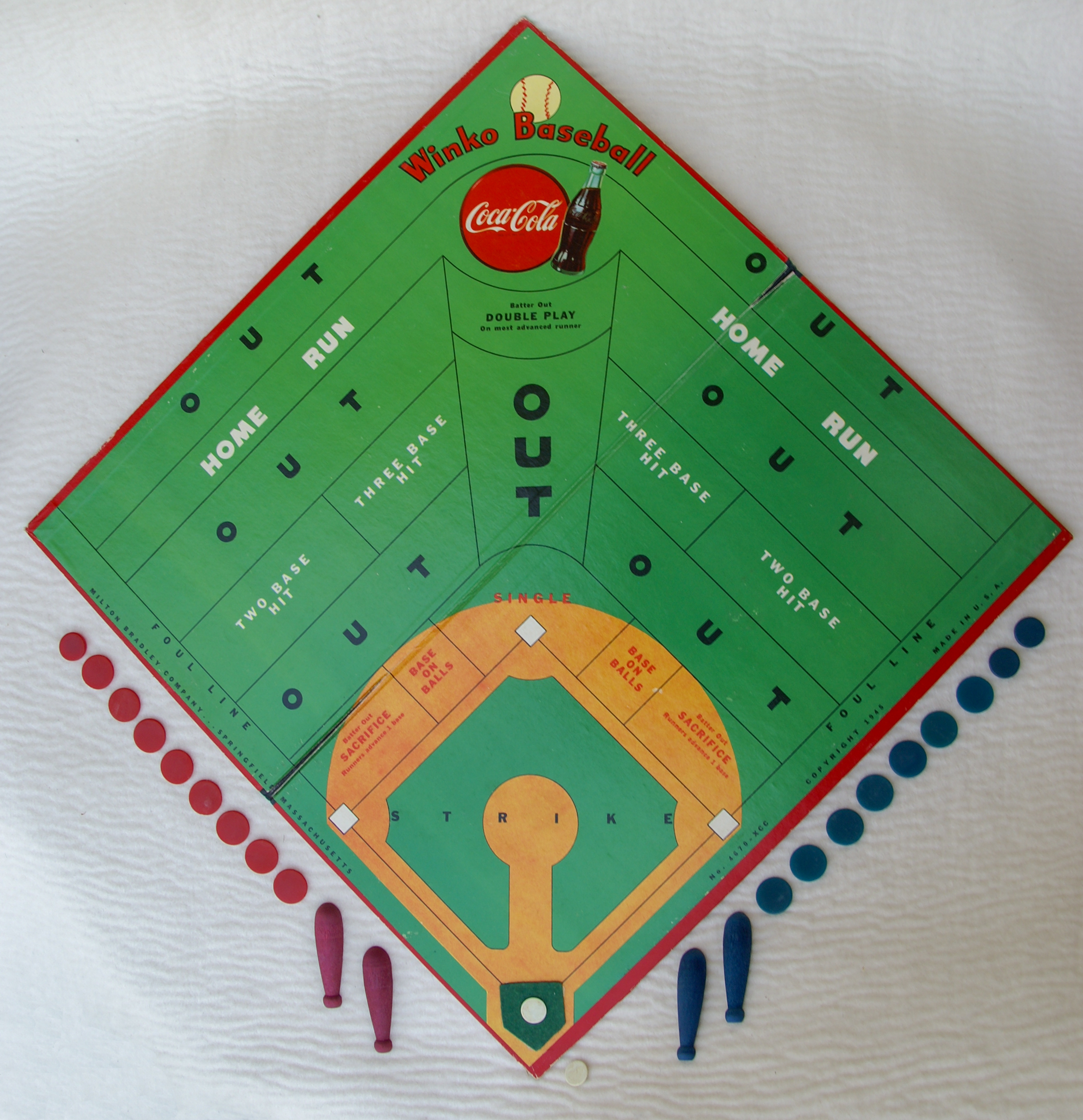

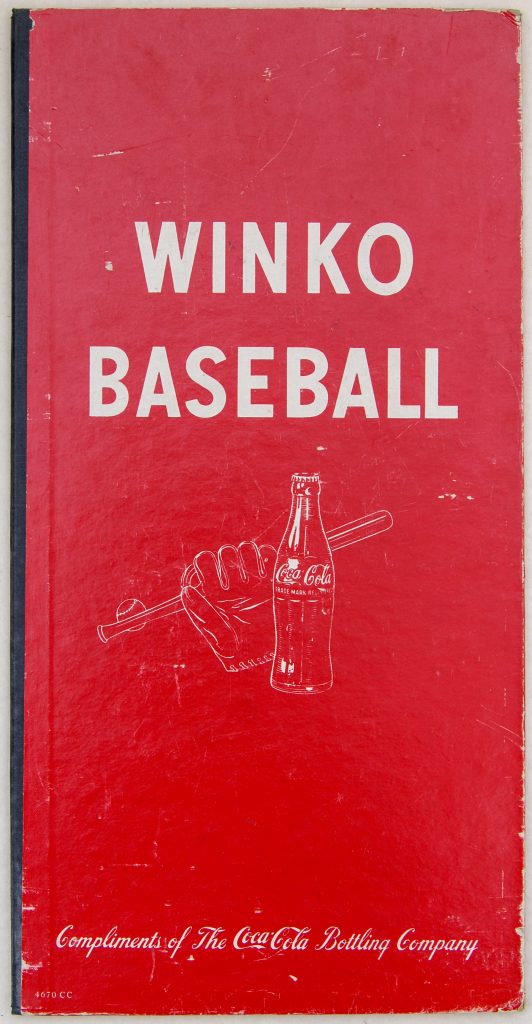

Lest we forget: baseball was not left off the list of sports for which a tiddlywinks version was created. Patent 1,217,908 was issued to Charles B. Brewer and Harvey E. Haines on 6 March 1917 (application filed on 21 February 1914) for a tiddlywinks version of baseball. And a decade later, Chester W. Brown was granted patent 1,548,507 on 4 August 1925 (filed 16 April 1923). Each of these patents is dominated by a baseball field laid out on a board or felt. Winko Baseball [19] was published by Milton Bradley in the 1940s and also came out in an edition with the Coca-Cola brand.

Rick Tucker Tiddlywinks Collection

Licenseable per Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

large, square box • rules label attached under box lid

Rick Tucker Tiddlywinks Collection

Licenseable per Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

Rick Tucker Tiddlywinks Collection

Licenseable per Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

Coca-Cola premium edition

large, square box • game board front with winks and wooden bat squidgers

Rick Tucker Tiddlywinks Collection

Licenseable per Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

Coca-Cola premium edition

large, square box • back of game board

Rick Tucker Tiddlywinks Collection

Licenseable per Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

![[+template:(Tucker Tw ID • [+xmp:title+] — publisher • [+iptc:source+] — title • [+xmp:headline])+]](https://tiddlywinks.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/BRA-44-DSC07223-scaled.jpg)

Coca-Cola premium edition

scoresheet

Rick Tucker Tiddlywinks Collection

Licenseable per Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

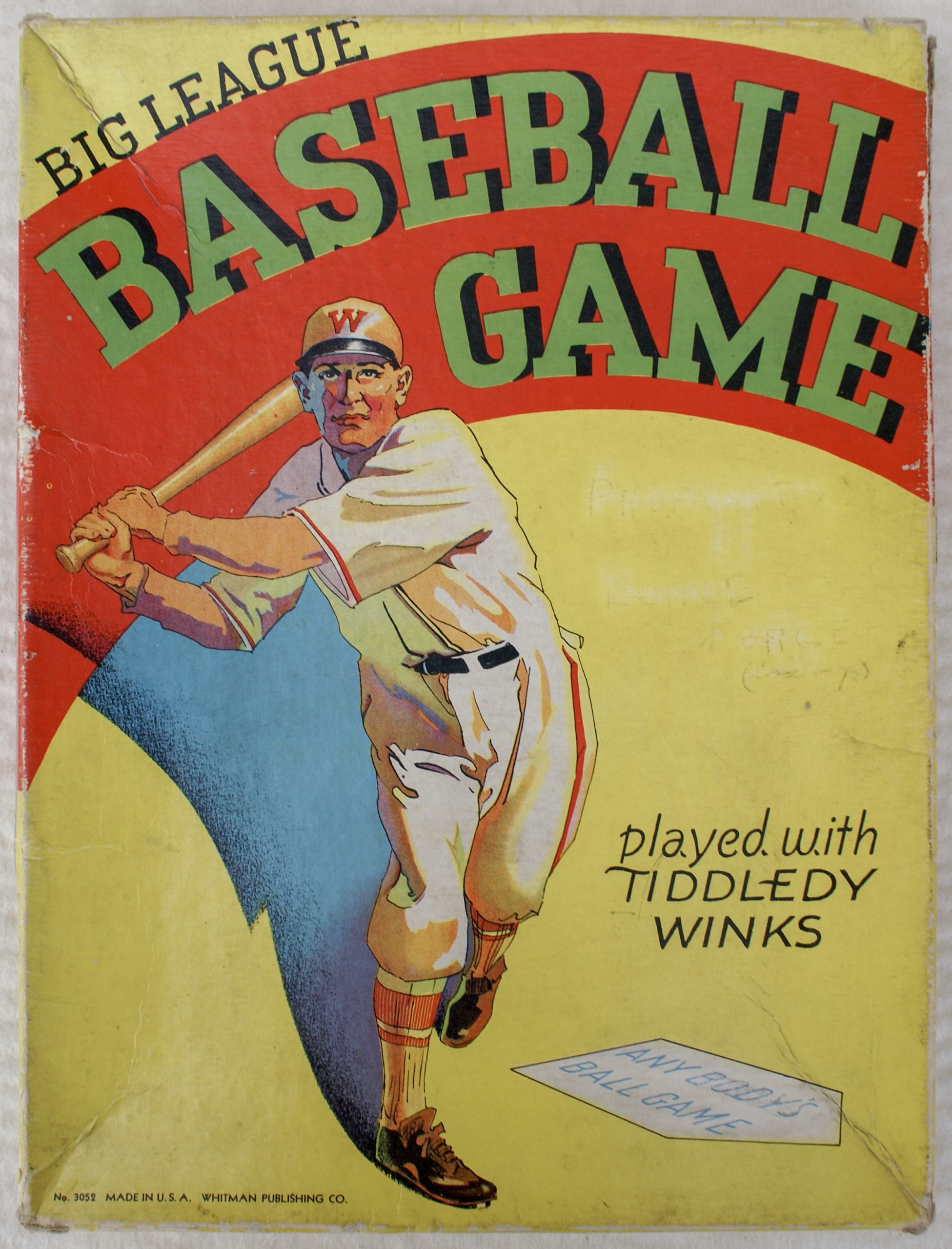

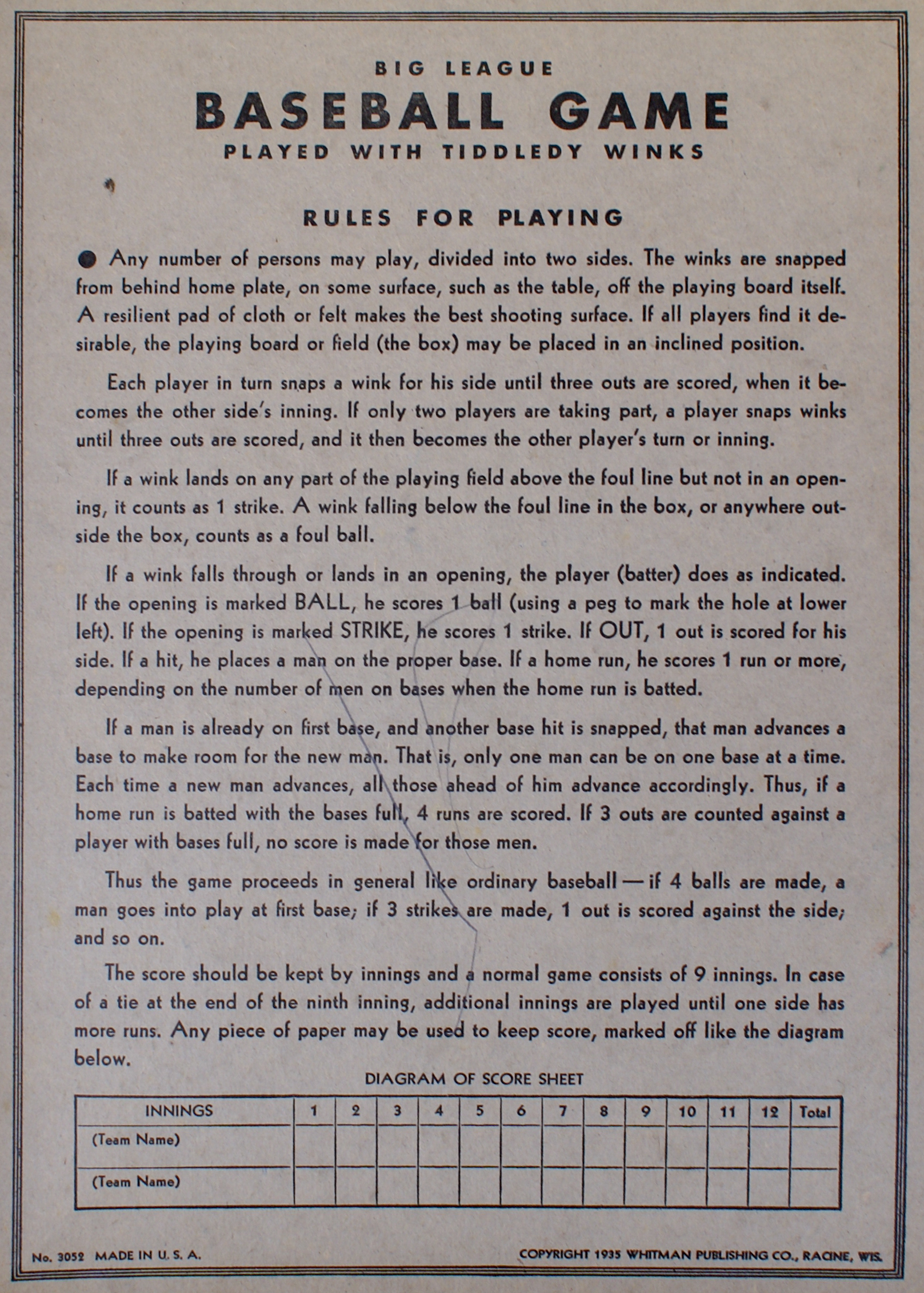

And Whitman/Western Publishing produced BIG LEAGUE BASEBALL GAME played with TIDDLEDY WINKS [20] in 1935.

Rick Tucker Tiddlywinks Collection

Licenseable per Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

rules printed under box lid

Rick Tucker Tiddlywinks Collection

Licenseable per Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

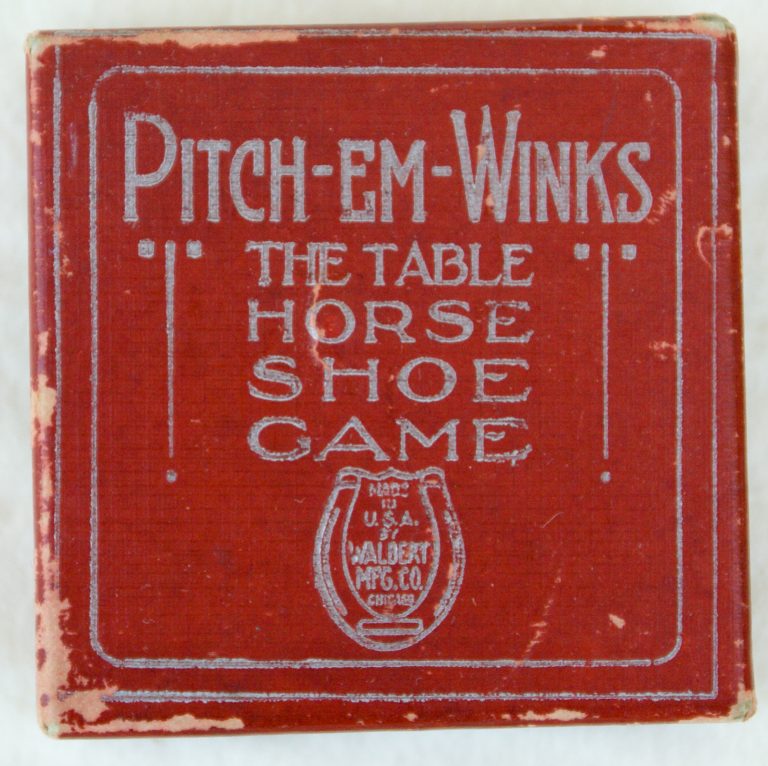

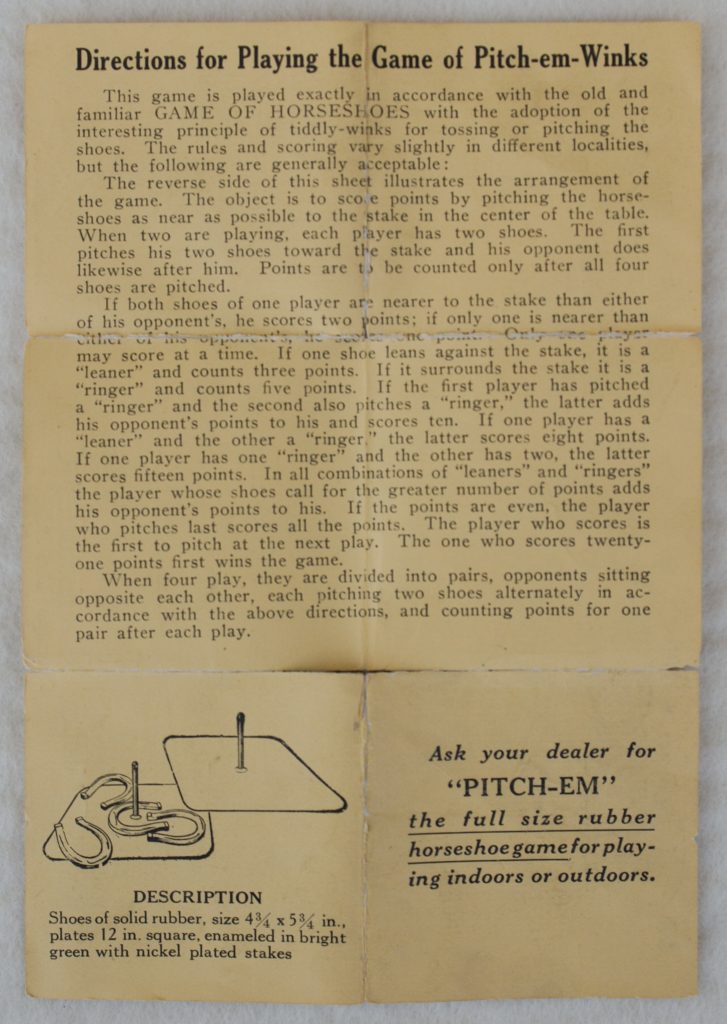

Horseshoe-shaped winks were claimed in a patent by Clarence Comstock (# 1,525,167, 1925), and were marketed by Walbert Manufacturing as Pitch-em-Winks the table horse shoe game and also sold by Sears Roebuck. This game is one of very few that have both metal (aluminum) shooters (discs) and winks (horseshoe-shaped).

Rick Tucker Tiddlywinks Collection

Licenseable per Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

Rick Tucker Tiddlywinks Collection

Licenseable per Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

Rick Tucker Tiddlywinks Collection

Licenseable per Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

Numerous basketball tiddlywinks games have surfaced since this article was written in 1996, including three varieties made by McLoughlin Bros. in the 1910s, and some by Whitman Publishing.

Update date: 11 July 2022

(American) Football, of course, was not spared. Three American patents are known, each issued in 1928 to Sidney G. Hands, Morris E. Yaraus, and Alfred Hustwick, individually. Morris E. Yaraus in his Indoor Parlor Miniature Football Game had each “disk convexed on one side and concaved on the other side, a stylus adapted to move the [disk] horizontally along the said gridiron when brought in contact with the convexed edge of said [disk], and to raise the [disk] in an arc when contacted with the concaved side.” And again, no editions are yet known. Wherefore are these things hid? [21]

And soccer (European football) and hockey round out (well, not quite) the tiddlywinks sports simulations. The Chad Valley Games produced THE GREAT INDOOR GAME “SCRUM” around 1913 for European football enthusiasts, and American Leonard. F. Pierson patented a soccer version in 1918. Another American soccer patent was granted in 1977, to Enrique G. Duch. A hockey patent snuck in in 1979 to Anibal Romero and George Spector.

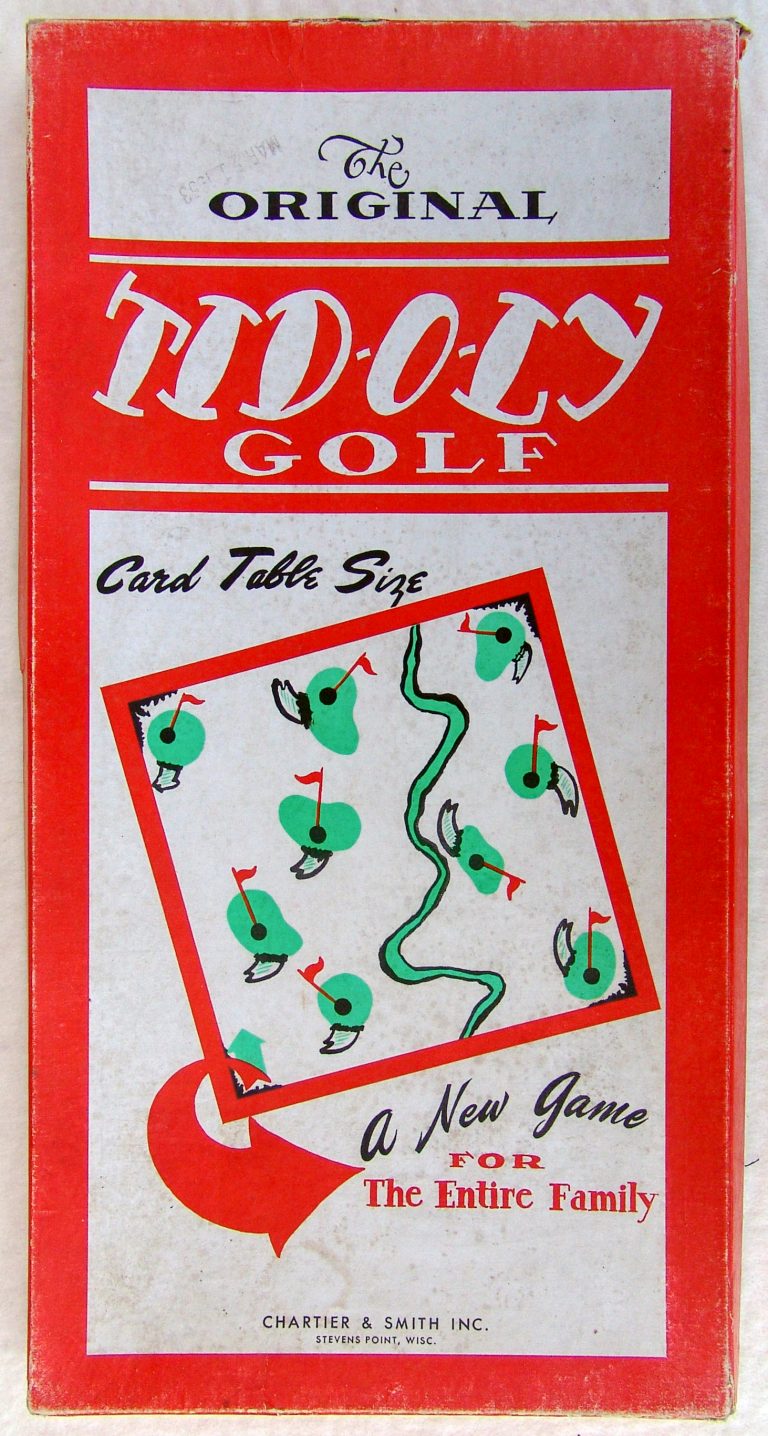

Returning to golf: Two separate US patents were issued in 1902, one to Harry T. Coldwell, and one to Arthur F. Knight. Then 1925 (Henry Van Arsdale Jr.), 1932 (Elizabeth and Louis Livingston), 1950 (Vincent A. Freeman), and 1972 (James M. Park). None of these have been seen as boxed games. One known version is Chartier & Smith’s The ORIGINAL TID-O-LY GOLF, © 1949. TiddlyLinks was used in commerce 6 March 1962 by Raymond L. Eddy, Muncie, Indiana, and registered as a trademark on 31 March 1964 (# 767,481) but later canceled due to a conflict with another trademark.

Rick Tucker Tiddlywinks Collection

Licenseable per Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

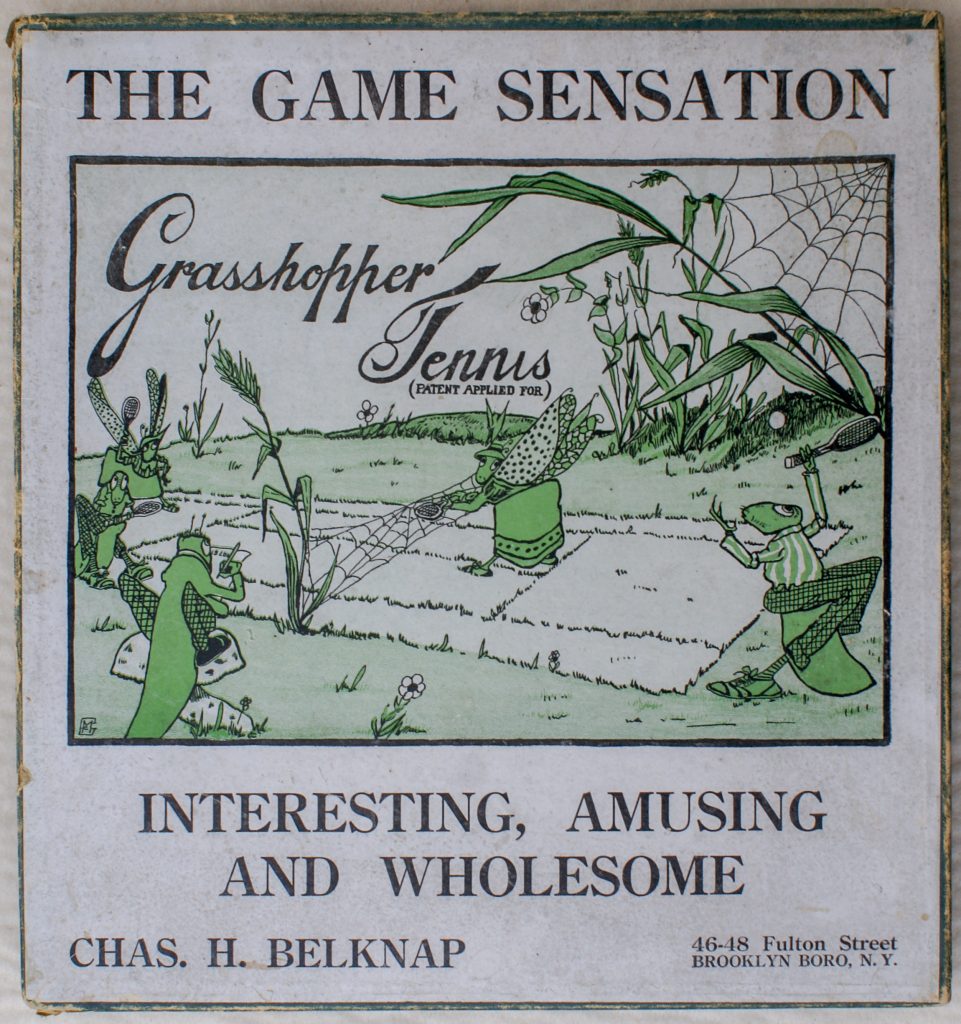

After Horsman’s Tiddledy-Winks Tennis appeared in 1890, other tennis editions have also been sought after. Chas. H. Belknap produced Grasshopper Tennis in 1916, with the box opening to a full tennis court marked on green felt including a sewn net, and with wooden shooters shaped like tennis rackets. Sears also sold this edition in 1919.

Rick Tucker Tiddlywinks Collection

Licenseable per Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

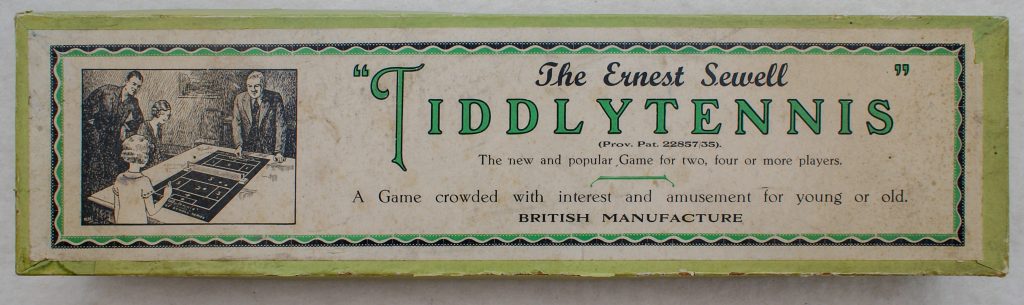

A British version, The Ernest Sewell “TIDDLYTENNIS” (Hoey collection) from Ernest Sewell’s London Magical Co., appeared in 1936, and was patented there. A leaflet included with this game calls it “THE WORLD’S GREATEST 1936 CRAZE! The Game that interested H.R.H. The Duke of Kent, at the British Industries Fair, Feb. 20th, 1936.”

Rick Tucker Tiddlywinks Collection

Licenseable per Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

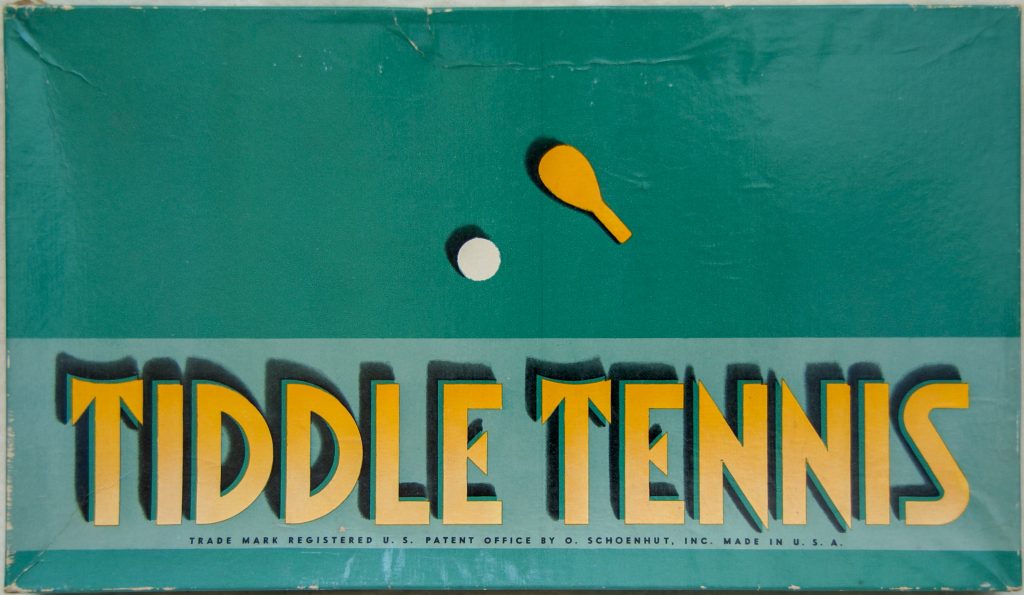

And back in the U.S., Charles K. Van Riper patented a tennis layout in 1937 (# 2,069,487). O. Schoenhut, Inc. produced TIDDLE TENNIS in 1938, which is the same year he obtained a trademark for the name. Only two U.S. patents exist for tiddlywinks tennis.

Rick Tucker Tiddlywinks Collection

Licenseable per Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

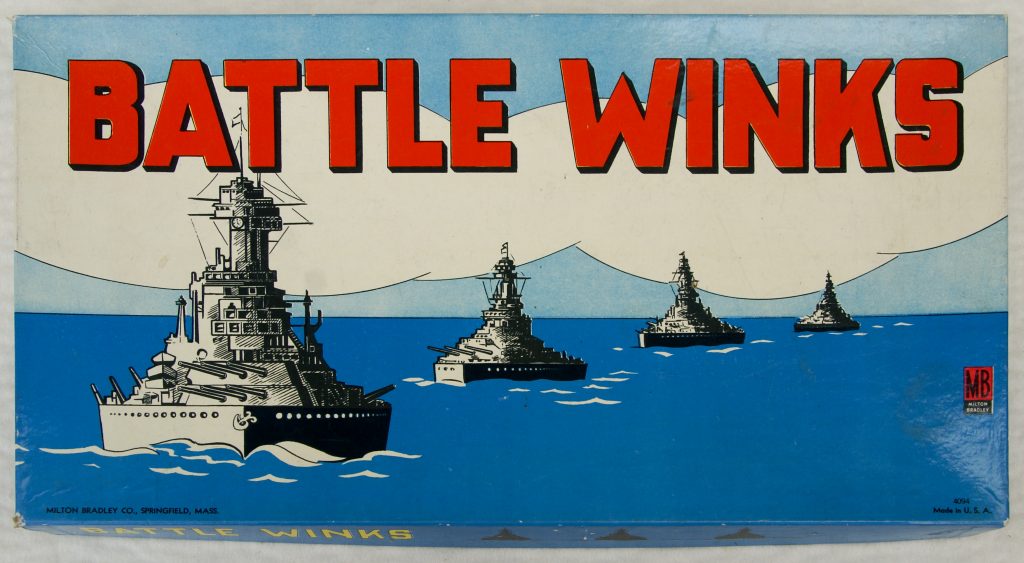

Off to War

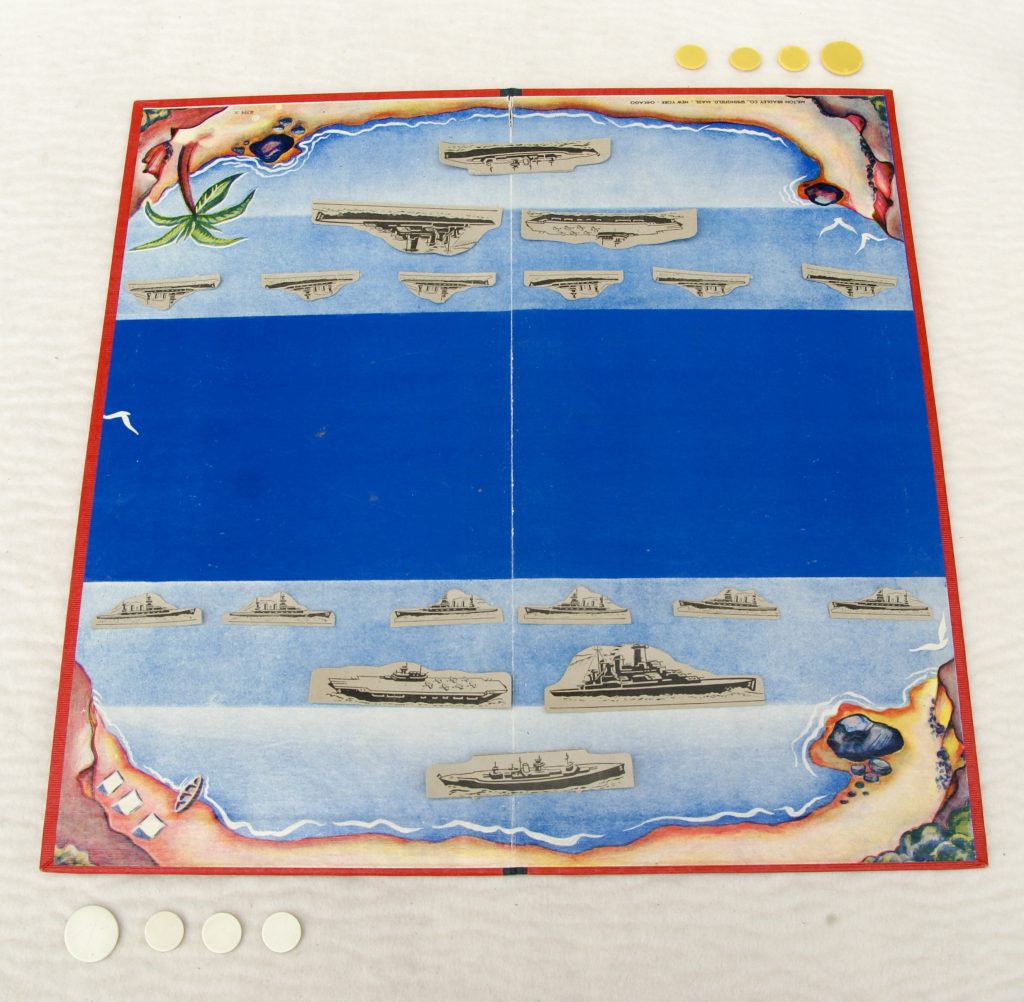

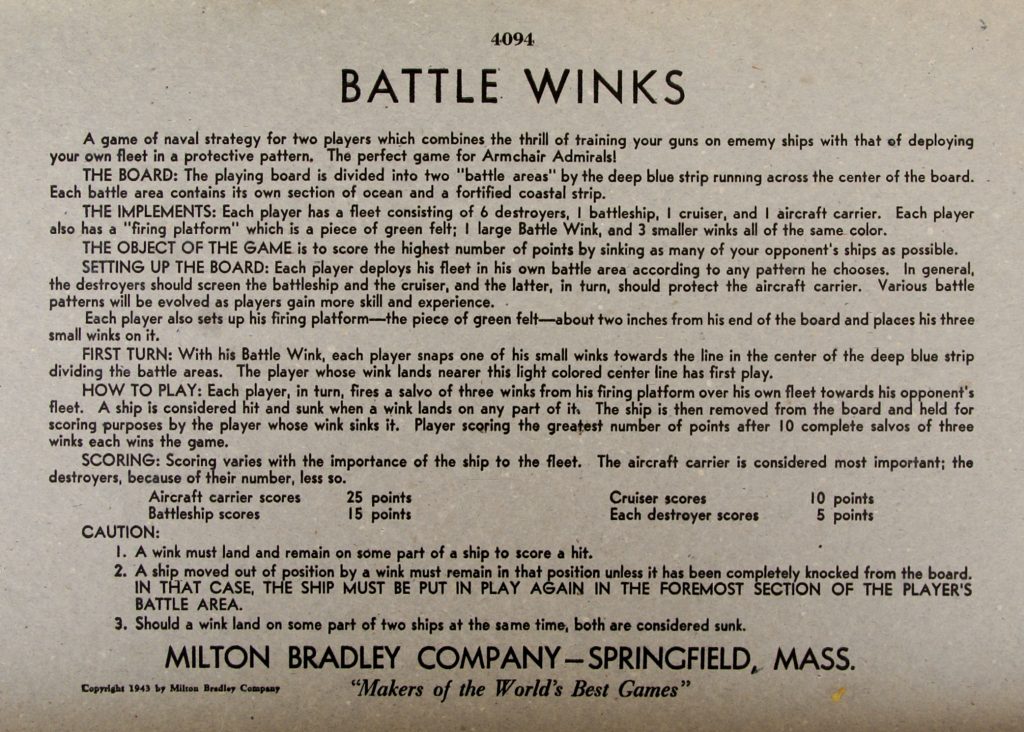

Rick Tucker Tiddlywinks Collection

Licenseable per Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

Rick Tucker Tiddlywinks Collection

Licenseable per Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

Rick Tucker Tiddlywinks Collection

Licenseable per Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

Corey Games (East Boston, Massachusetts) produced Tiddly Winks BARRAGE GAME (© 1941) where, according to the rules, “Players place the winks, one at a time on the BATTERY EMPLACEMENT. Each team now shoots his winks as fast as possible (without waiting for turns), in an endeavor to land the winks in the opponent’s seaport, munitions dump, air field, or capitol. […] any player who lands one wink in his opponent’s capitol wins immediately.”

Rick Tucker Tiddlywinks Collection

Licenseable per Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

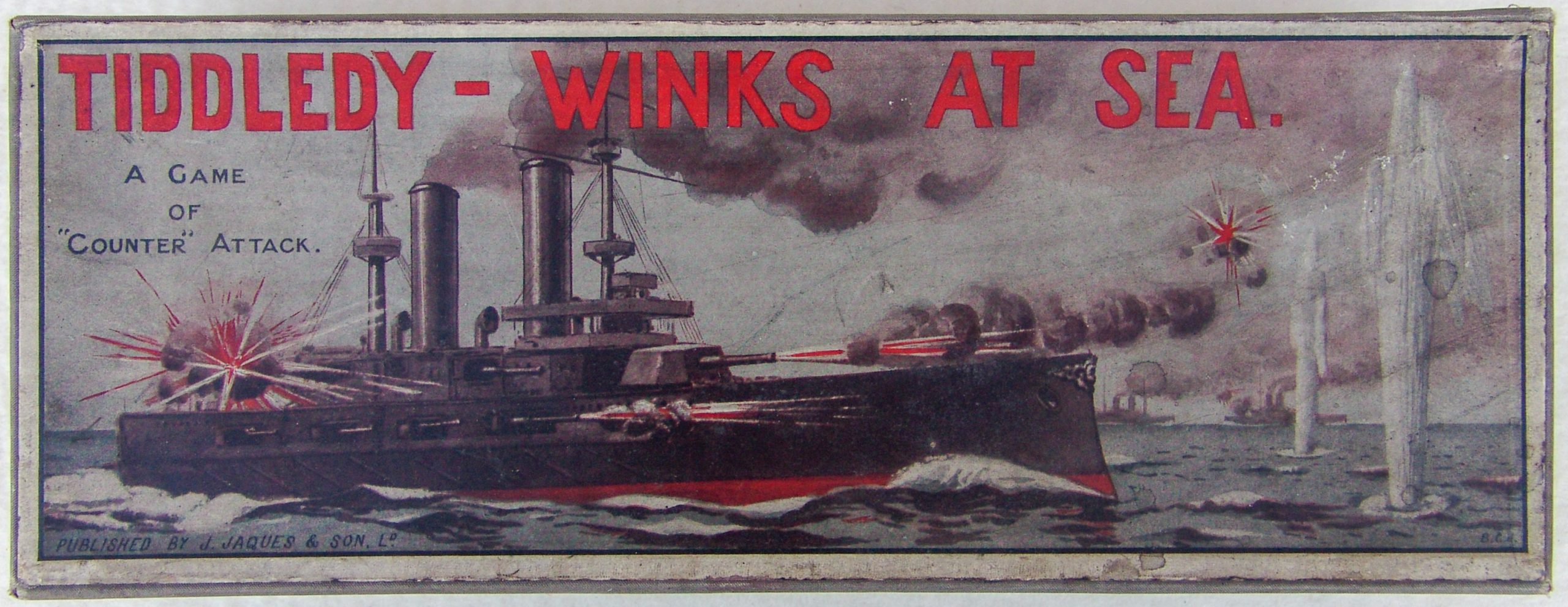

Several British varieties are known, including two patents (John Alfred Rivington in 1899 for a naval/land battle, and Robert Colin Harvey Webb for a war simulation in 1967), and J. Jaques & Son’s TIDDLEDY-WINKS AT SEA in 1913: “The Old Game of Tiddley (sic) Winks made very interesting with the Model of a Battleship. The scoring being taken from the different part[s] on which the shots land.” [23]

Rick Tucker Tiddlywinks Collection

Licenseable per Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

Bruce Whitehill [24] has loaned me a boxless set (of perhaps pre-1920 vintage) consisting of a yellow-orangeish felt mat with marked stations for wooden battleships. Each battleship has three metal spires onto which rings are to be shot.

Tiddlywinks Target Practice

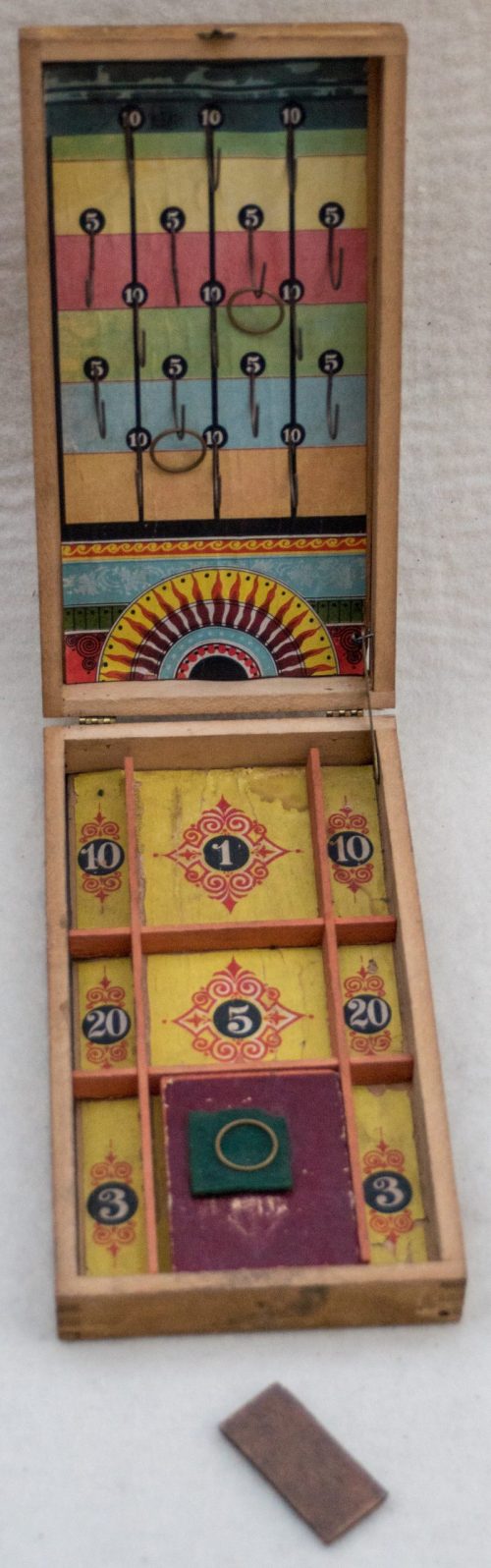

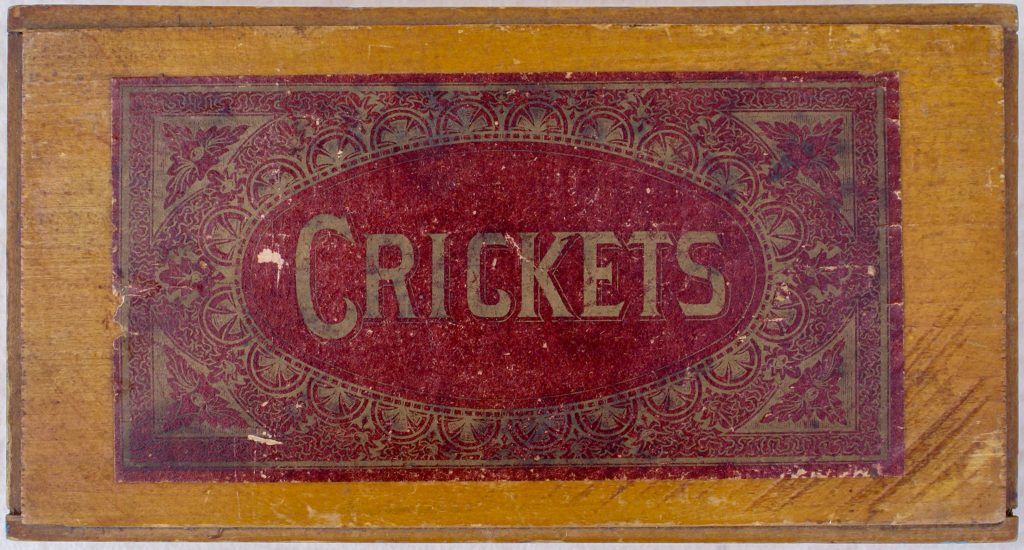

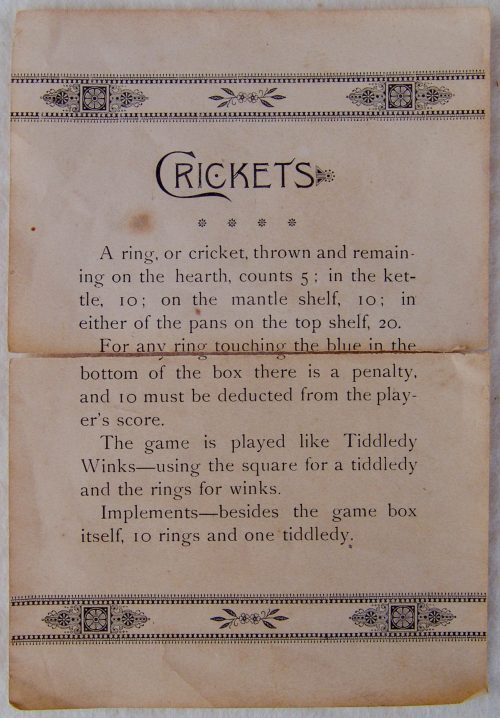

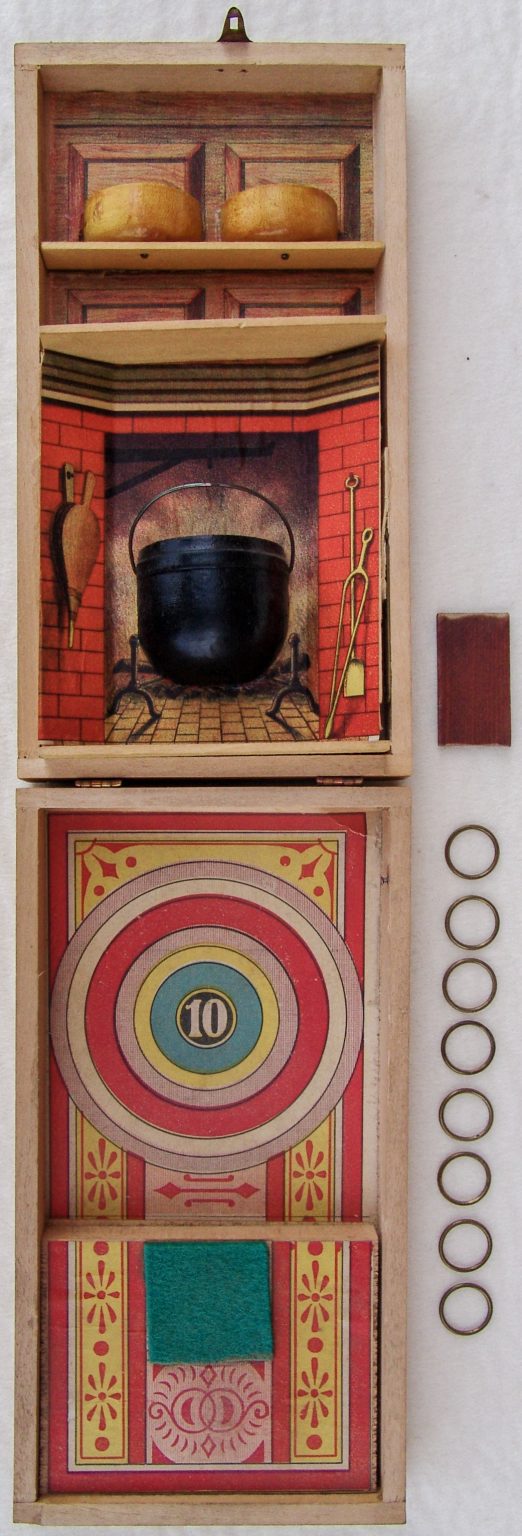

Selchow and Righter debuted a series of wooden tiddlywinks sets with intriguing targets, as indicated in an advertisement (page 417) and article (page 503) in The American Stationer of 27 August 1891. Each edition was 25 cents or $2.00 a dozen, and each was housed in a wooden box with a hinge.

Snap Dragon, in which rings are shot using rectangular shooters, with hooks as targets

Pedro, where rings are shot at a clown with an open mouth target as well as hooks on his ears and nose

Cricket on the Hearth (or simply Crickets), with five different editions, where discs are shot to land in cauldrons or on top of the mantel of a fireplace

Juno, where rings are shot toward cups and pins with numbered values

Since the publication of this article in 1996, an additional wooden set in this series has been discovered:

Milk Maid, where rings are shot to land in the milkmaid’s apron or in a cup atop her head

While these games were sold by Selchow & Righter as jobbers, none of them have a publisher name marked on them.

Update date: 11 July 2022

Rick Tucker Tiddlywinks Collection

Licenseable per Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

inside top and bottom with rectangular brown bone squidger and metal quoit wink on green felt

Rick Tucker Tiddlywinks Collection

Licenseable per Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

inside bottom, shooting a metal quoit wink with rectangular brown bone squidger

Rick Tucker Tiddlywinks Collection

Licenseable per Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

Rick Tucker Tiddlywinks Collection

Licenseable per Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

Rick Tucker Tiddlywinks Collection

Licenseable per Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

Rick Tucker Tiddlywinks Collection

Licenseable per Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

Rick Tucker Tiddlywinks Collection

Licenseable per Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

inside top and bottom plus brown rectangular squidger and metal quoit winks

Rick Tucker Tiddlywinks Collection

Licenseable per Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

Seven years after the appearance of Pedro and Snap Dragon, Johannes Klauder obtained a patent (# 611,915) for a game in which rings were caught by hooks in his Ring Game (1898). And in a different twist, in William R. Purnell’s patent (# 1,520,082) for a Radio Game (1924), a wink has a hook on it, and is to be propelled to catch on a wire.

Some patented targets are invitingly complex, such as that of Charles Zimmerling (# 477,287, patented 1892) which I hope to find somewhere. It is a vertical circular board on which is mounted a “king cup” and 19 “general cups”, plus a chute to a separate cup. Each cup “may be of different tones, which, as is evident, will be pleasantly apparent when the chips strike or enter the same.”

![[+template:(Tucker Tw ID • [+xmp:title+] — publisher • [+iptc:source+] — title • [+xmp:headline])+]](https://tiddlywinks.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/US000477287-Zimmerman-illustration.png)

While no Zimmerling editions have been found, Zimmerling did indeed copyright a photograph entitled “Propelling the Disc” in 1892, a drawing of the same name in 1893, and a print of “The Parlor Target” in 1895. This provides circumstantial evidence that Zimmerling tiddlywinks sets were actually produced and lends some hope that they will ultimately turn up in my collection.

A similarly musical tiddlywinks set of Victorian vintage is reported by Brian Jewell [25]: a “Tiddlywinks Tower [which] was a miniature bell tower made from either tin plate or wood. The object was to flick the tiddlywink into one of the window openings and so ring the bell.”

![[+template:(Tucker Tw ID • [+xmp:title+] — publisher • [+iptc:source+] — title • [+xmp:headline])+]](https://tiddlywinks.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/UK_Patent_5482_year-1892_p2-1-642x1024.jpg)

Rectangular pieces were used in George H. Johnson’s Ballot-Box Game patent (# 1,539,357, 1925) where the discs have “one State designated on each side thereof, a number thereone corresponding to the number of electoral votes…, the sides of said discs also representing the two principal parties.”

In Barn Yard Tiddledy Winks (1930, publisher not given on box, but reported to be Parker Brothers in Lee Dennis [26] and elsewhere), the objective is to shoot winks so they knock down the barn yard animals, including a cow, goat, sheep, and chicks. A set with an analogous target set-up is E. I. Horsman’s Over the Garden Fence (Lilly Library, Indiana University [27]), although the main objective in this game is to land in specific areas such as in a fountain.

Robert B. Mars (1969, #3,429,572) marked discs with “letters of the alphabet, or numbers or words or mathematical symbols.” Then there is Emerson F. Maryn’s Mathematical Tiddly-wink Apparatus (1975, #3,881,728) in which winks are made of two parts, pivotally connected, so that “after all players have taken their turns then each player…. Opens each wink to expose the mathematical formula imprinted thereon. Each player must then work the mathematical forumla to arrive at the correct solution. … The winner of the game is the player having the highest mathematical score such that the player with the most winks in the container is not necessarily the winner.

An innovative variety of the early 1970s is Kanga Winks (currently being unearthed in a basement archaeological dig in Silver Spring, Maryland), whereinwhich a kangaroo’s pouch is the target.

![[+template:(Tucker Tw ID • [+xmp:title+] — publisher • [+iptc:source+] — title • [+xmp:headline])+]](https://tiddlywinks.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/AVO-01_Avon_Kangawinks_check-if-dupe.jpg)

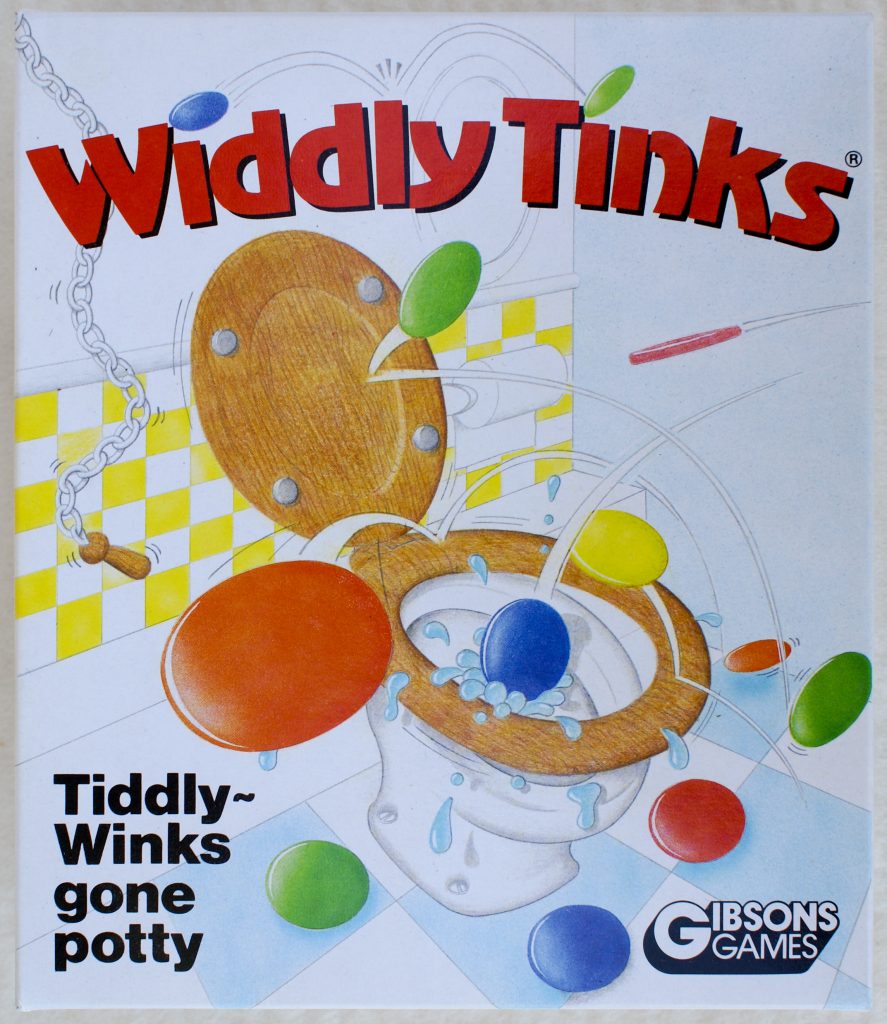

And, in the it-had-to-happen category, is Gibsons Games’ Widdly Tinks (around 1992) in which a loo (i.e., a toilet) is the target for the winks.

Rick Tucker Tiddlywinks Collection

Licenseable per Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

Of course, the reviled (to many game collectors, though not by me) ultra-common tiddlywinks sets put out by Milton Bradley, Parker Brothers, Whitman, and scores of other publishers have simple targets such as a cup or a cardboard layout marked with concentric circles and numbered values. Often, the same set inside will appear with dozens of very different cover art versions over a decade or more.

The Adult Party Game and The Children’s Game

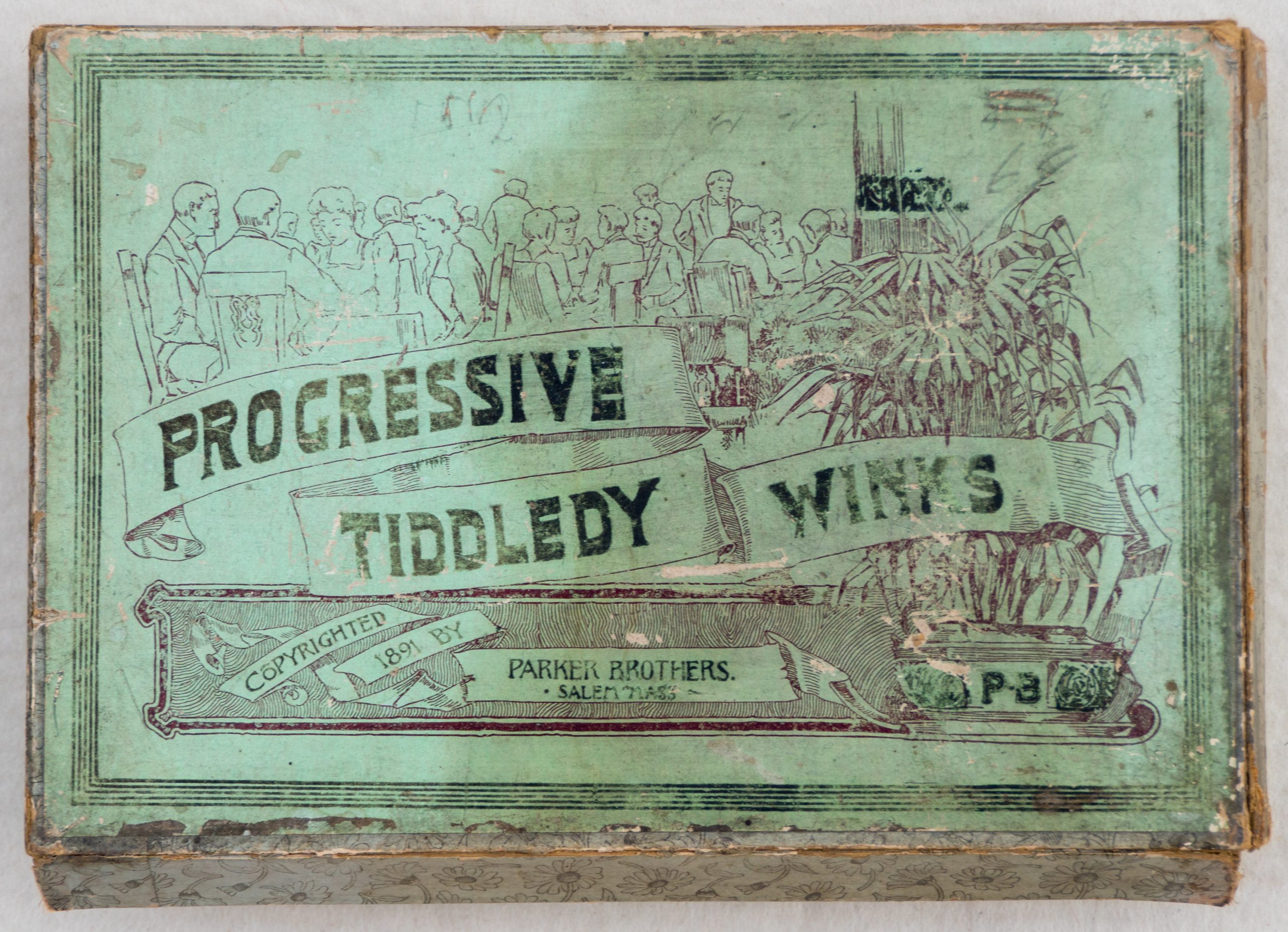

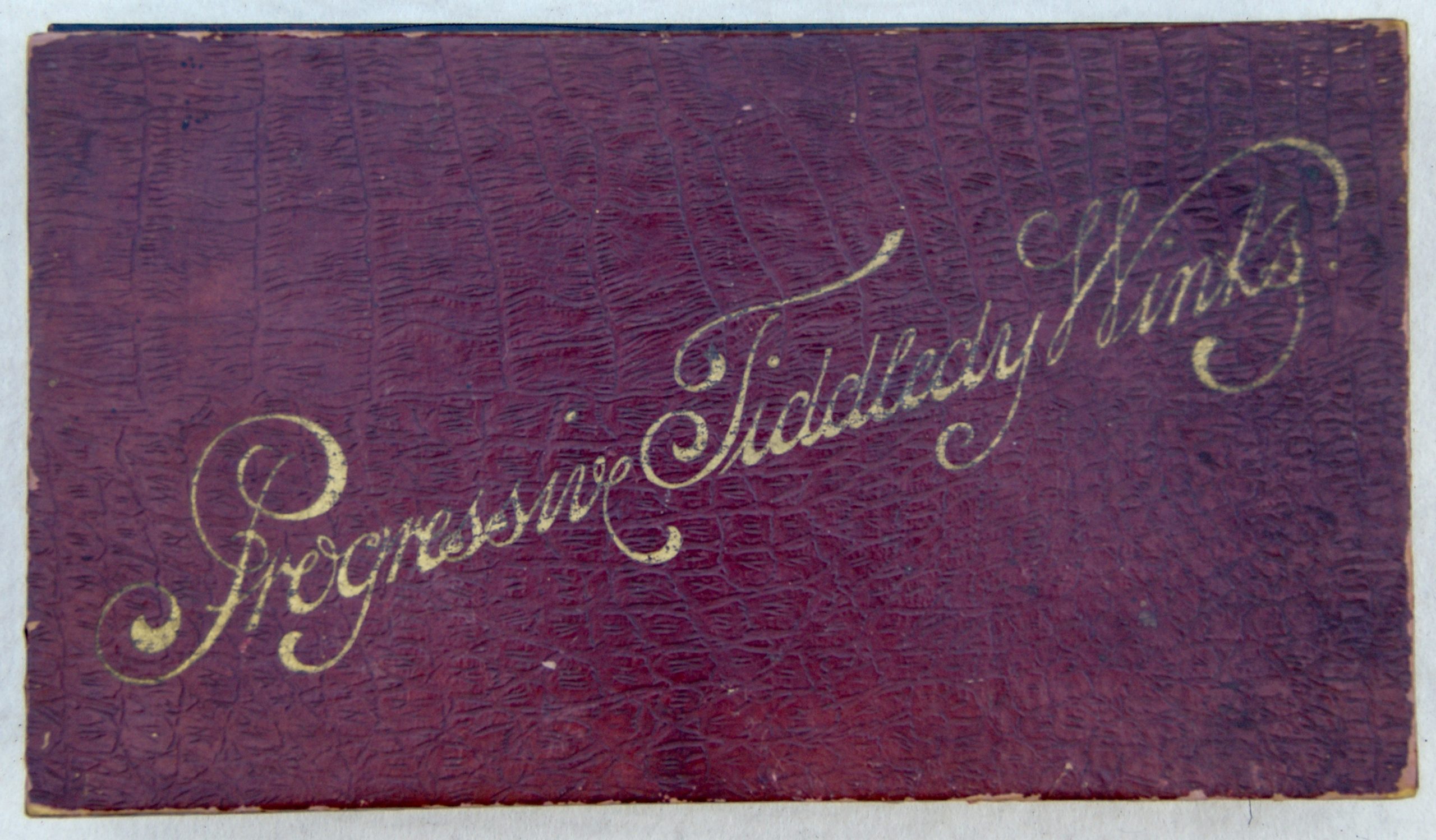

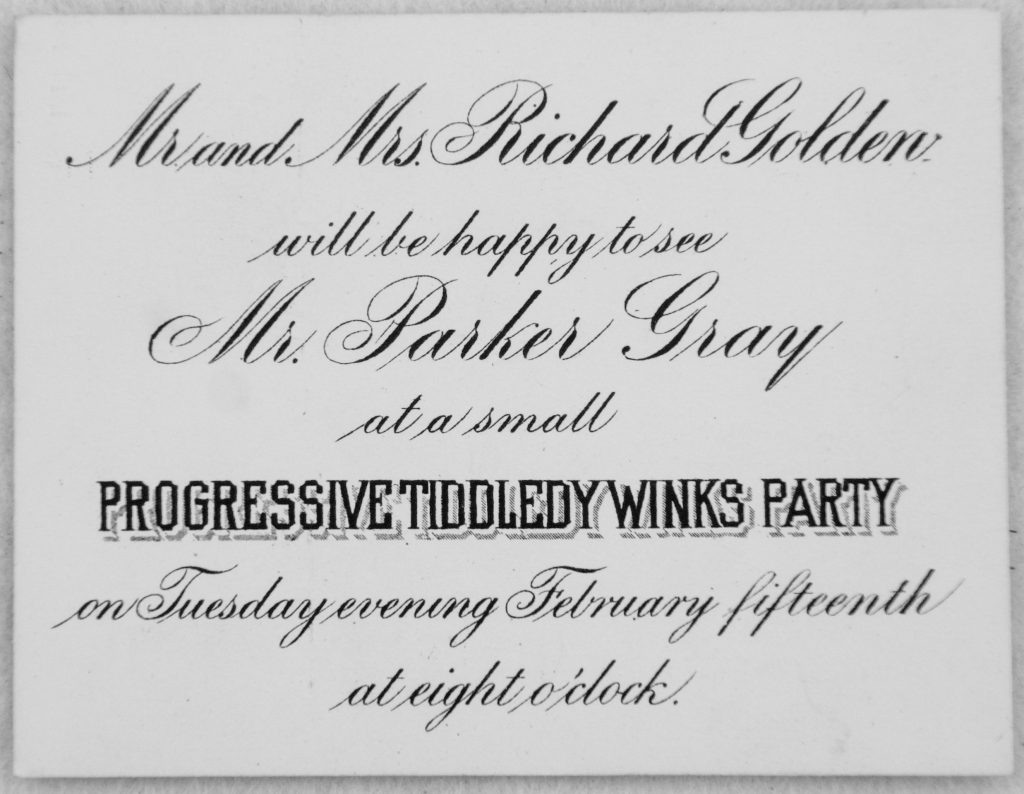

In the early 1890s, tiddlywinks was principally an adult game, and parties were held to play Progressive Tiddledy Winks (mentioned in the Young Folks Cycloædia cited earlier, 7 November 1890).

The Parker Brothers Progressive party edition (© 1891) contained 4 full sets, scorecards, and gold, silver, and red stars. In this game, “partners who win at the head table each place a gold star upon their score cards. Partners who lose at the booby table place a red star upon their score cards. Partners who progress at any of the tables each place a silver star upon their cards. […] Royal, Progressive, and Booby prizes may be awarded to those having the largest number of respective stars.”

Rick Tucker Tiddlywinks Collection

Licenseable per Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

Rick Tucker Tiddlywinks Collection

Licenseable per Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

Rick Tucker Tiddlywinks Collection

Licenseable per Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

McLoughlin Bros. also sold a Progressive Tiddledy Winks set, which was sold for $3.00 according to an ad in The American Stationer (19 February 1891). McLoughlin copyrighted “Progressive Tiddledy Winks, Rules and Suggestions” on 7 March 1891.

Rick Tucker Tiddlywinks Collection

Licenseable per Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

Rick Tucker Tiddlywinks Collection

Licenseable per Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

Rick Tucker Tiddlywinks Collection

Licenseable per Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

And from correspondence of Lady Emily Lutyens (grand-daughter of Bulwer-Lytton), writing on 24 April 1892 at the age of 17:

After dinner we all played the most exciting game that ever was invented, called Tiddleywinks. It consists in flipping counters into a bowl, and being a good number we played at two tables, one table against another, and the excitement was tremendous. I assure you everyone’s character changes at Tiddleywinks in the most marvelous way. To begin with, everyone begins to scream at the top of their voices and to accuse everyone else of cheating. Even I forgot my shyness and howled with excitement. Con darted aroung the room snatching at counters, screaming and trembling with excitement. Lord Wolmer flicked all the counters off the table and cheated in every possible way. George was very distressed at this and conscientiously picked every counter up again. Even Gerald got fearfully excited and was quite furious because someone at his table knocked over the bowl just as all the counters were in. […] I assure you no words can picture either the intense excitement or the noise. I almost scream in describing it. [28]

Rick Tucker Tiddlywinks Collection

Licenseable per Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

![[+template:(Tucker Tw ID • [+xmp:title+] — publisher • [+iptc:source+] — title • [+xmp:headline])+]](https://tiddlywinks.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/ATA-01-cover-DSC09671-2-3-1024x1021.jpg)

Rick Tucker Tiddlywinks Collection

Licenseable per Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

![[+template:(Tucker Tw ID • [+xmp:title+] — publisher • [+iptc:source+] — title • [+xmp:headline])+]](https://tiddlywinks.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/ATA-01-shooting-quoit-at-target-DSC09679-2-1024x832.jpg)

squidging a quoit wink at the circular numbered target

Rick Tucker Tiddlywinks Collection

Licenseable per Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

Rick Tucker Tiddlywinks Collection

Licenseable per Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

Even in the early 1890s, tiddlywinks was already well on its way to becoming a children’s game. The reknowned author of juvenile tales, John Kendrick Bangs, wrote two books with tiddlywinks featured as the main characters. In Tiddledywink Tales (1891):

"Perhaps that’s a little too deep for you Jimmieboy," Blackey added, "but you see we Tiddledywinks have to jump as a matter of business. We jump for a living, so when we come to our sports we try to do something different." (page 171)

![[+template:(Tucker Tw ID • [+xmp:title+] — publisher • [+iptc:source+] — title • [+xmp:headline])+]](https://tiddlywinks.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/1890_John-Kendrick-Bangs_Tiddledywink-Tales_p158.png)

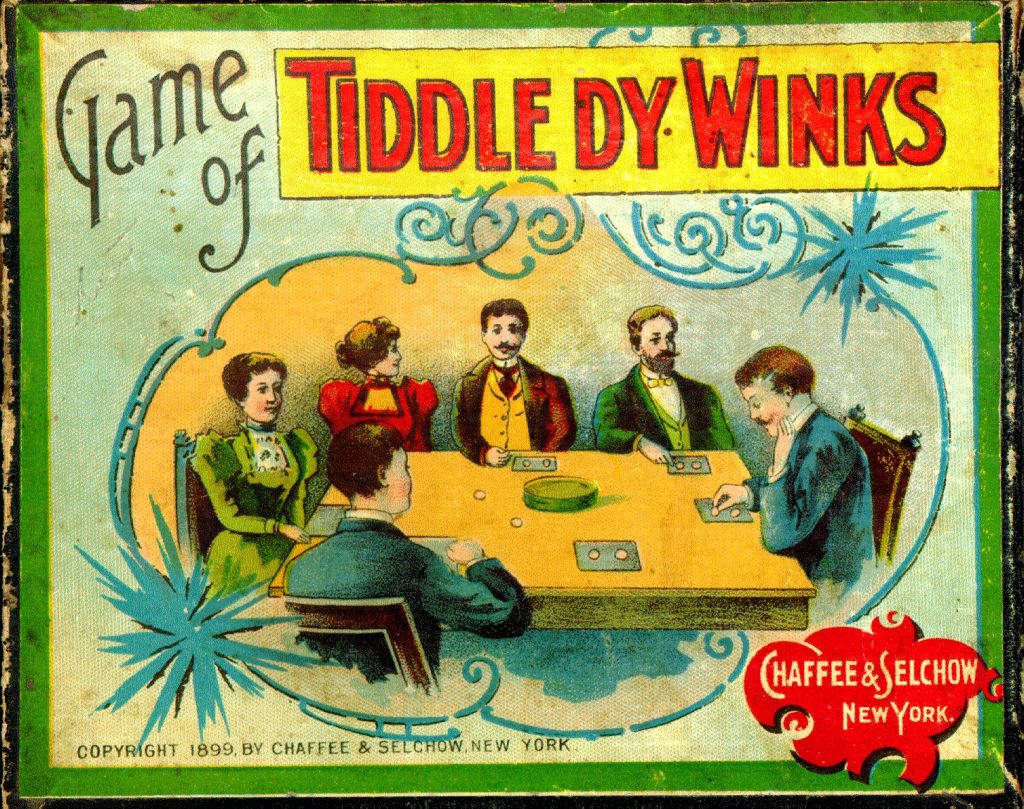

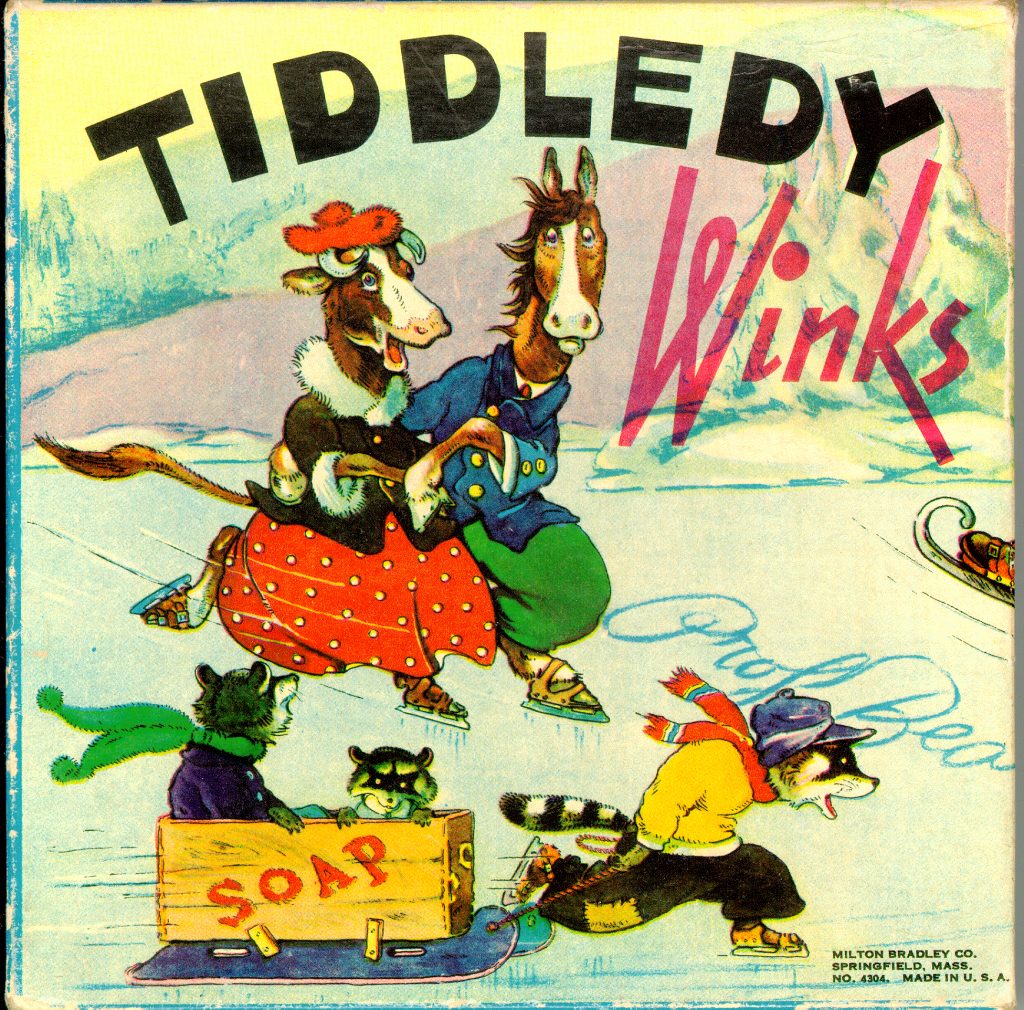

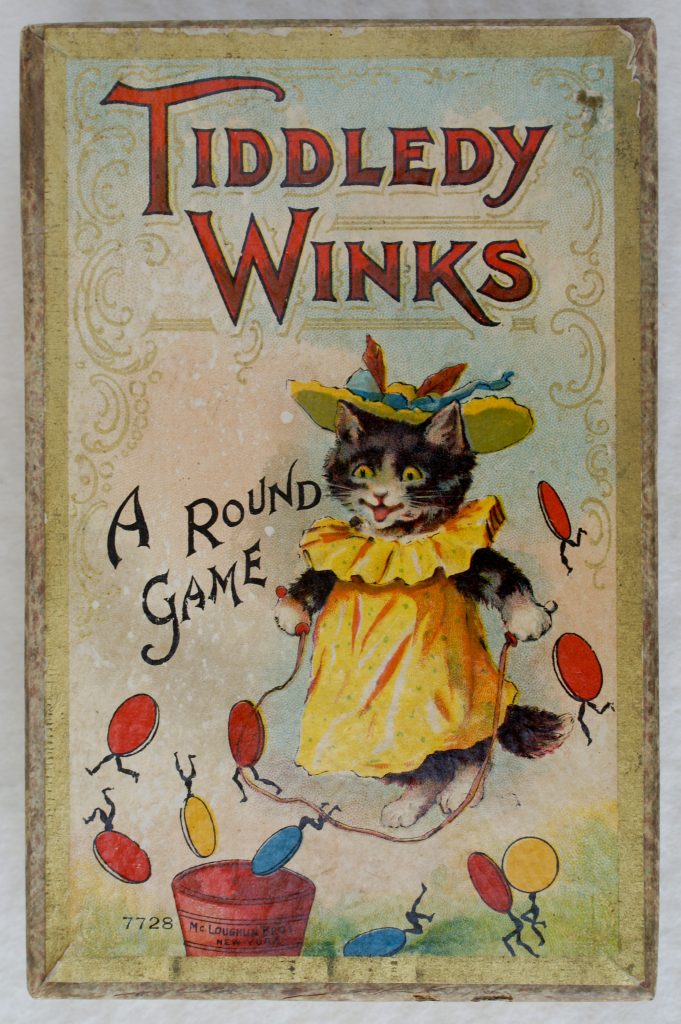

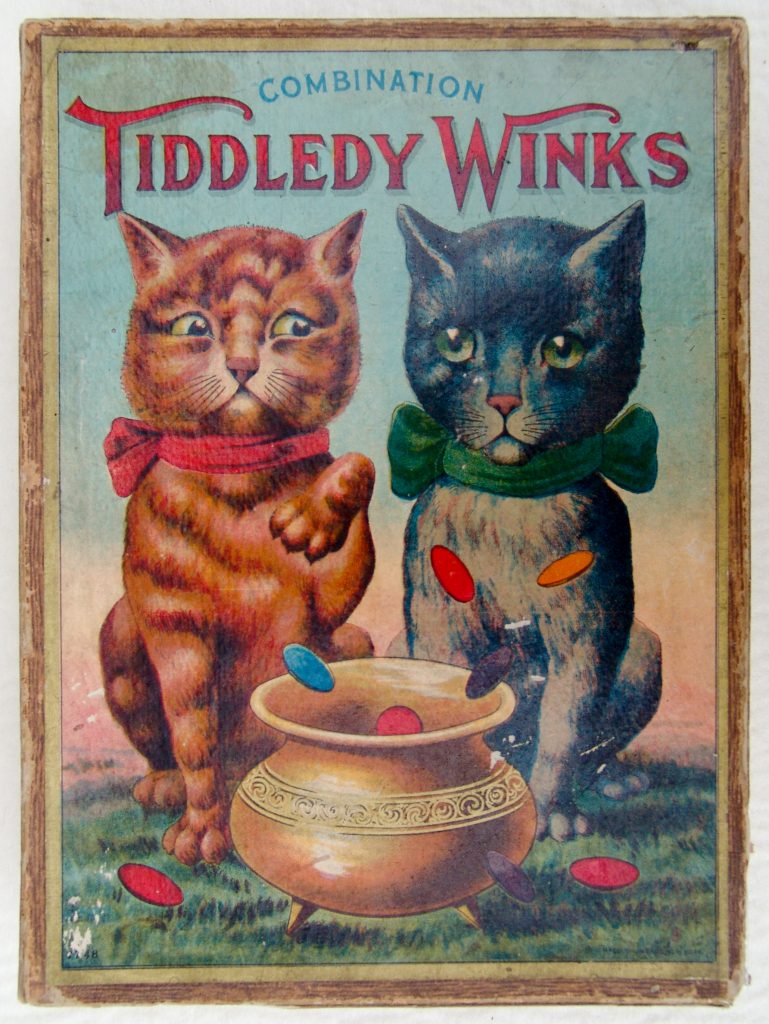

Animals are a favorite topic for the cover art, undoubtedly designed to appeal to children. In my collection, there are cats, dogs, crickets, elephant, monkey, frog (McLoughlin’s Tiddledy Winks patent pending and patented 18 Nov. 1980), pigs, grasshopper, stork, rabbit, fleas and there’s one cover that has chipmunks, a cow, and a horse skating (Milton Bradley # 4304, Tiddledy Winks, with artwork by H. Boylston Dummer). The sought-after Combination Tiddledy Winks with two cats on the cover is known both as a McLoughlin Bros. title (# 7748) and as a Milton Bradley title (# 4404), from the 1910s. A more precious McLoughlin cat cover (Tiddledy Winks A Round Game (# 7728), early 1890s, depicts a smiling cat jumping rope along with dancing winks.

Rick Tucker Tiddlywinks Collection

Licenseable per Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

Rick Tucker Tiddlywinks Collection

Licenseable per Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

Rick Tucker Tiddlywinks Collection

Licenseable per Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

The Interlude

We look to tiddlywinks to get us back to the primeval simplicity of life

Reverend Edgar Ambrose Willis, the first Secretary of the English Tiddlywinks Association in 1958

(one of The London Observer’s Sayings of the Year).

MIT’s two saving graces are the tiddlywinks championship of North America and incredible graffiti

Playboy, September 1969, page 195.

The smart set of Des Moines (pop. 148,900), biggest city in Iowa, often amuse themselves with a parlor game: a modern variation of famed tiddle-dy-winks. […] It was invented by "that skillful player, John Cowles, 29, who is to Des Moines what a dynamo is to a powerhouse."

Time, 14 May 1928, page 26

(John Cowles was the publisher of the Des Moines Register and Tribune-Capital)

Tiddledy Winks. Shooting small disks into a cup by pressing quickly on the edge of the disks with another disk. Chief elements: Unusual Activity, Dexterity, Rivalry.

The Pedagogical Seminary, Volume 7, Number 4, page 473, December 1900

in which 79 out of 3958 boys and 120 out of 4760 girls expressed a fondness for the game. (marbles being 603 of boys/56 of girls, and baseball 2697 of boys/245 of girls)

Equipment Evolution

The box or container for tiddlywinks was made of wood on a few occasions in the 1890s, but was mostly of cardboard. Most were rectangular boxes, but some are roughly cylindrical containers, and a mushroom-shape is popular.

For cup targets, wood was used in most early editions, such as the McLoughlin ones in the early1890s; glass started appearing for example in the Parker 1897 editions (although some are wood), and then one of basket weave, and then of course, all too soon, the inaudible and noiseless foot of time [29] ensued, and plastic took over. True is it that we have seen better days. [30]

Winks, as stated before, were made, at various points in time, of ivory, wood, vegetable ivory, celluloid, metal, and plastic.

And concluding this brief section: shooting surfaces were in the early McLoughlin era of sewn flannel and felt; and shortly after of large felt playing surfaces (Hop Scotch, naval simulation, Grasshopper Tennis, etc.). Later, the shooting pads were small felt pieces of medium thickness, and in the past decade or so, the ultracheap sets have had no felt or hard, thin felt.

Advertising, Premiums, & Promotions

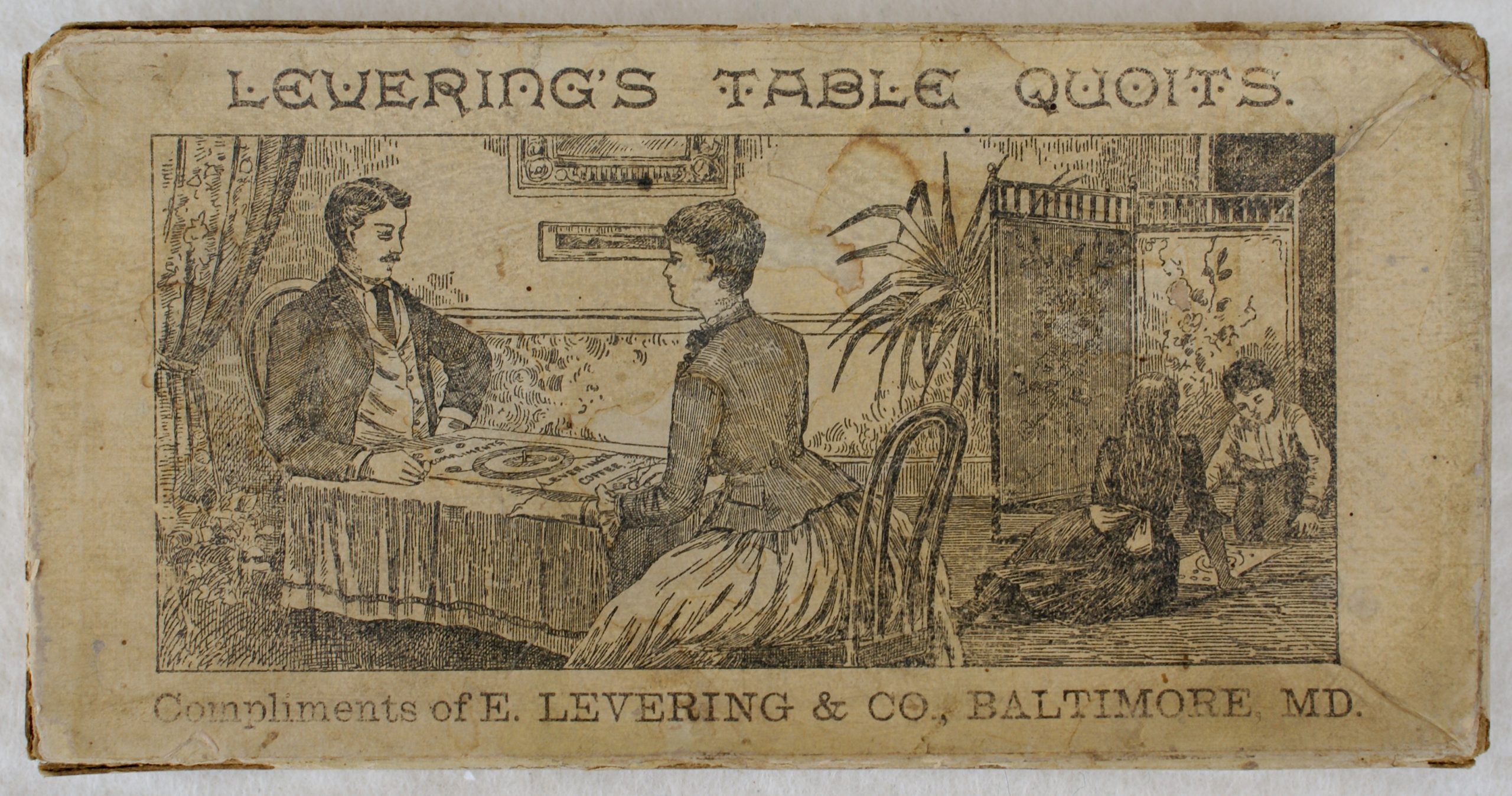

All consumers of LEVERING’S RELIABLE "E. L. C." Roasted Coffee can easily obtain one of these games [Levering’s Table Quoits, early 1890s], without any expense to themselves by sending us Twenty (20) of the Monograms E. L. C. (as below) cut from the face of one (1) pound packages of our "E. L. C." Roasted Coffee.

E. Levering & Co., Importers, Jobbers & Roasters of Coffee, Baltimore MD (Est. 1842)

This promotional game comes with a very nice felt playing surface (also advertising Levering’s Coffee) which has a thin wooden stick coming up through the middle of the mat. The winks that are played are not discs but instead are rings (also called quoits).

Rick Tucker Tiddlywinks Collection

Licenseable per Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

![[+template:(Tucker Tw ID • [+xmp:title+] — publisher • [+iptc:source+] — title • [+xmp:headline])+]](https://tiddlywinks.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/GEN-01-container-and-winks-DSC06420-1024x588.jpg)

Rick Tucker Tiddlywinks Collection

Licenseable per Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

Rick Tucker Tiddlywinks Collection

Licenseable per Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

Pascal Pontremoli of Paris, France has kindly alerted me to several French premium editions: Le Clown, Jeu de Puces in Pif Gadget number 290, and a Pif surprise #1275 (gadget 37), a winks version of European football, “Foot”, from 1969. (By the way, jeu de puces means tiddlywinks, and literally translates as game of fleas. That’s true for tiddlywinks in most Romance and Slavic languages.) Plus a Procter & Gamble (France) tiddlywinks set included as a Bonux laundry detergent bonus in 1984.

Other Matters

For Further Information

This article only squidges the tip of the iceberg of our tantalizing tiddlywinks heritage. What’s past is prologue. [31] Further information is available. Please contact Rick Tucker particularly if you have tiddlywinks sets for sale!

And visit Tucker’s tiddlywinks web pages at

References

[1] Attributed, in Joseph Strutt, The Sports and Pastimes of the People of England, 1801

[2] William Shakespeare, Henry IV, Part II, Act III, I, 80.

[3] Lillie Struble, letter in Library Journal, 15 April 1978, page 790.

[4] William Shakespeare, Julius Caeser, Act III, ii, 188.

[5] ARTnews, January 1980, page 85.

[6] James A. Mackay, Childhood antiques, 1976, page 76.

[7] British Airways magazine, date unknown.

[8] Jean Piaget, The Grasp of Consciousness—Action and Concept in the Young Child, 1976 (French version: 1974), pages 124-125.

[9] William Shakespeare, As You Like It, Act II, vii, 139.

[10] Merriam Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, 10th edition, © 1993.

[11] William Shakespeare, As You Like It, Act I, ii, 97.

[12] Trade Marks Journal (England), 15 May 1889, page 476.

[13] William Shakespeare, Hamlet, Act II, ii, 211.

[14] William Shakespeare, King Henry the Fifth, Act III, I, 31.

[15] William Shakespeare, As You Like It, Act I, I, 126.

[16] William Shakespeare, Twelfth Night, Act III, I, 68.

[17] William Shakespeare, Twelfth Night, Act II, iv, 6.

[18] Antique Toy World, September 1987, cover, with Bruce Whitehill’s collection.

[19] Mark Cooper, Baseball Games: Home Version of the National Pastime 1860s-1960s, © 1995, page 102.

[20] Rarities magazine, July/August 1982, page 64.

[21] William Shakespeare, Twelfth Night, Act I, iii, 135.

[22] Ruth and Larry Freeman, Cavalcade of Toys, © 1942, page 366.

[23] A. W. Gamage Ltd, Gamage’s Christmas Bazaar, 1913, page 222.

[24] Bruce Whitehill, Games: American Boxed Games and Their Makers, 1822-1992, with Values, © 1992, Wallace-Homestead, Radnor PA, many pages.

[25] Brian Jewell, Sports and Games: History and Origins, 1977, pages 108-109.

[26] Lee Dennis, Antique American Games, 1991 edition, Page 170.

[27] Games Researchers’ Notes,No. 22, February 1996, pages 5505-06.

[28] Lady Emily Lutyens, A Blessed Girl, Lippincott, 1953, pages 97-98.

[29] William Shakespeare, All’s Well That Ends Well, Act V, iii, 41.

[30] William Shakespeare, As You Like It, Act II, vii, 120.

[31] William Shakespeare, The Tempest, Act II, I, 261.

Other references are included in the main text, particularly many references to The American Stationer in 1890 and 1891.

© 2022 North American Tiddlywinks Association. All Rights Reserved | Hosted at Elementor.Cloud

![[+template:(Tucker Tw ID • [+xmp:title+] — publisher • [+iptc:source+] — title • [+xmp:headline])+]](https://tiddlywinks.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/1888-11-08-UK-patent-16215-Joseph-Assheton-Fincher-adj-1024x648.jpg)

![[+template:(Tucker Tw ID • [+xmp:title+] — publisher • [+iptc:source+] — title • [+xmp:headline])+]](https://tiddlywinks.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/US000442438-1-1024x655.jpg)

![[+template:(Tucker Tw ID • [+xmp:title+] — publisher • [+iptc:source+] — title • [+xmp:headline])+]](https://tiddlywinks.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/1891-Parker-Brothers-catalog-pages-22-23-1024x834.jpg)

![[+template:(Tucker Tw ID • [+xmp:title+] — publisher • [+iptc:source+] — title • [+xmp:headline])+]](https://tiddlywinks.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/1891-Parker-Brothers-catalog-page-7-656x1024.jpg)

![[+template:(Tucker Tw ID • [+xmp:title+] — publisher • [+iptc:source+] — title • [+xmp:headline])+]](https://tiddlywinks.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/1891-Parker-Brothers-catalog-page-8-586x1024.jpg)